How Hospital Tube Systems Actually Work: A Guide for Operations Leaders

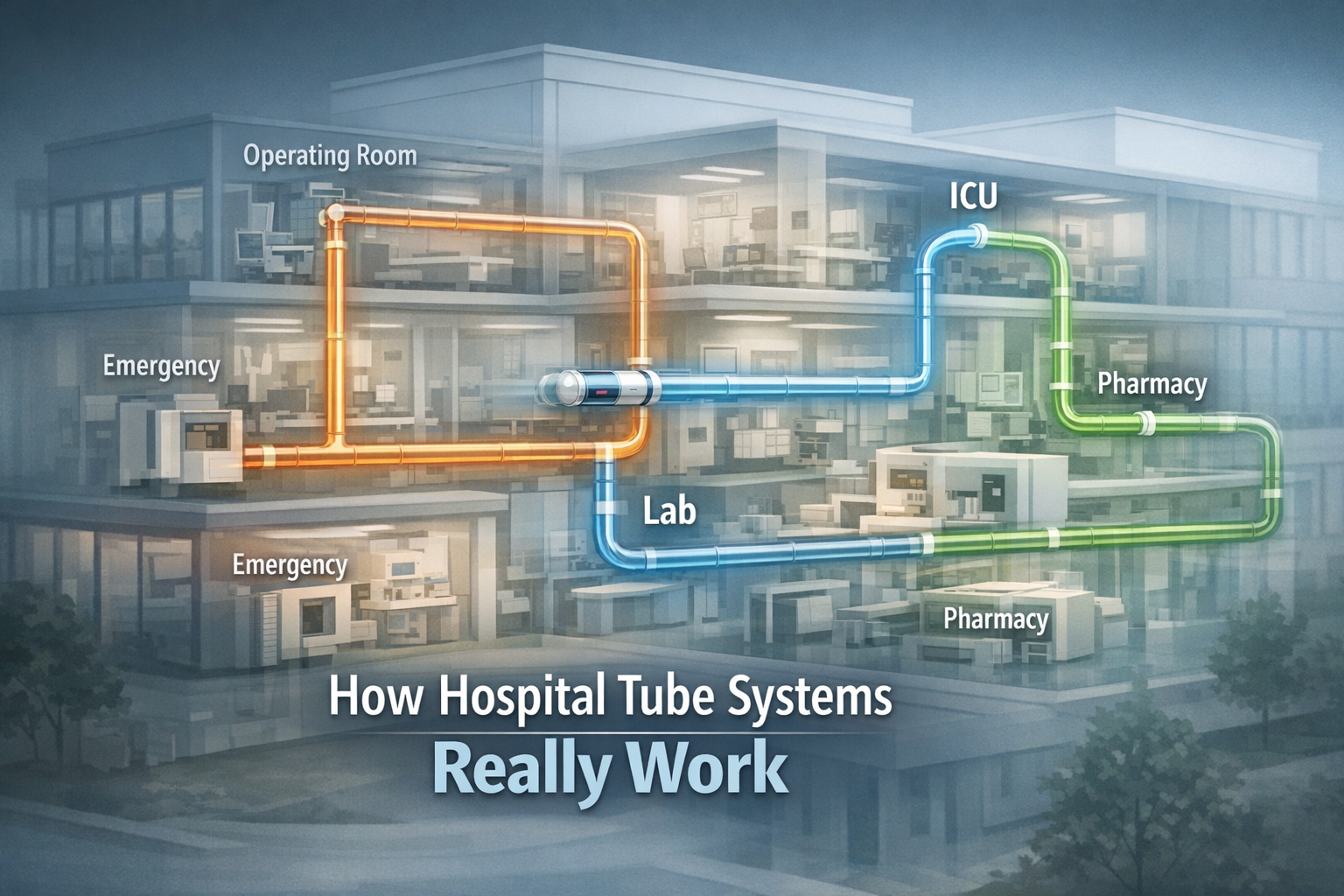

Hospitals move hundreds (sometimes thousands) of small but time-sensitive items every day: blood samples, medications, lab reports, blood products, documents, even small supplies.

In many facilities, those items still travel the old-fashioned way: carried by nurses, porters, or whoever happens to be heading in the right direction. It works. Until it doesn't. A misplaced specimen or slow delivery can delay treatment, extend length of stay, or force costly re-tests.

That's where a hospital tube system comes in.

This guide walks operations leaders, COOs, and facilities teams through how tube systems actually work inside a modern hospital: the core components, the journey of a carrier, and the design decisions that determine whether your system becomes a real advantage or just an expensive conveyor belt.

What Is a Hospital Tube System and Why Do Hospitals Use Them?

A hospital tube system (often called a pneumatic tube system) is an internal transport network that uses air pressure to move sealed carriers between stations throughout your facility.

Instead of a person walking a specimen from the ICU to the lab, a nurse places it in a carrier, docks it at a hospital tube station, and the system sends it directly to the lab station. Often in under a minute.

Many hospitals we've worked with see manual walks from ICU to lab take 7–10 minutes depending on elevator waits and staff availability. A well-designed tube route between the same points typically delivers in 60–90 seconds and does it consistently, 24/7.

Why Hospitals Use Tube Systems

For operations leaders, the value isn't speed alone. It's consistency and predictability. A well-designed tube system can:

Shorten turnaround times, especially lab TAT and STAT meds

Reduce nurse and porter time spent walking things around

Standardize transport workflows across departments and shifts

Improve traceability of high-value or time-sensitive items

Support 24/7 operations without adding headcount

If you regularly see nurses walking specimens across campus or hear complaints about "waiting on transport," you're already feeling the friction that a modern tube system hospital is designed to solve.

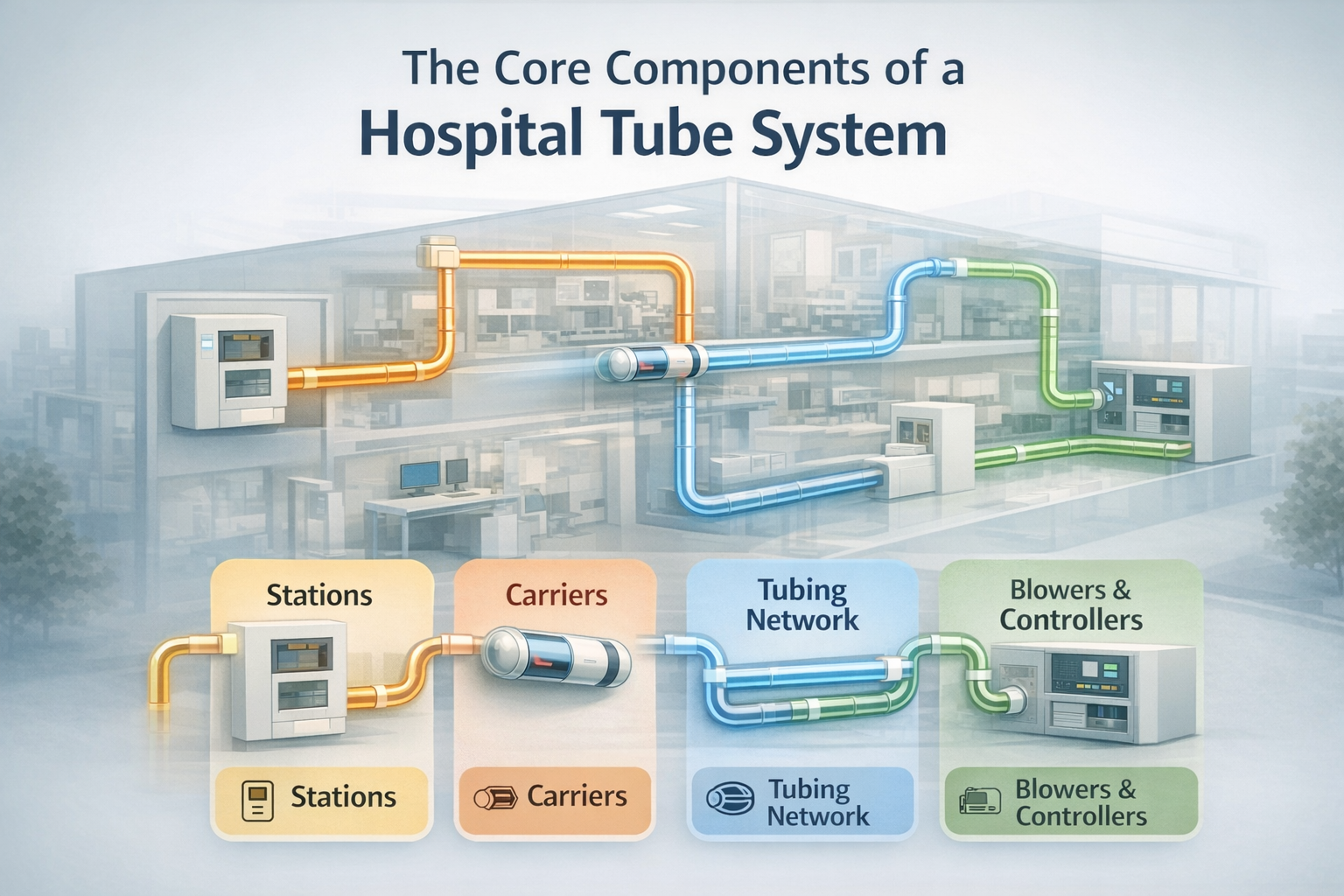

The Core Components of a Hospital Tube System

Even though every hospital layout is unique, most tube systems in hospitals share the same major building blocks.

1. Stations (Where Staff Interact)

Hospital tube stations are the visible, user-facing part of the system:

Wall or counter-mounted units in wards, ED, OR, pharmacy, lab, etc.

User interface (screen/keypad) to select destination or pick from presets

Doors or hatches where staff insert and remove carriers

For operations leaders, station design and placement influence how often staff actually use the system vs. bypassing it, safety and infection control (like separation of dirty/clean workflows), and noise, ergonomics, and congestion in high-traffic areas.

2. Carriers (What Holds the Payload)

Carriers are durable tubes (typically plastic with foam or other internal supports) that hold:

Blood and other lab specimens

Medications and IV fluids (within approved parameters)

Documents, reports, and small devices

Things to think about:

Proper inserts and cushions for specimens to avoid hemolysis or breakage

Color coding or labeling to distinguish item types and routes

Easy cleaning or disinfection protocols

3. Tubing Network (The Hidden Highways)

Above ceilings, in risers, or in dedicated shafts, a network of tubes forms the "highway" of your pneumatic tube system hospital:

Vertical risers connect floors

Horizontal runs connect departments on the same level

Bends, junctions, and diverters route carriers dynamically

Design choices here affect travel time between key points (like ED to Lab to ICU), capacity and congestion (how many carriers in motion before delays appear), and your ability to expand or add new stations during future retrofits.

4. Blowers & Controllers (The Engine and Brain)

To move carriers, tube systems use:

Blowers: Create positive and negative air pressure to push/pull carriers

Control units & software: Decide routes, manage priorities, and monitor performance

Modern control software can:

Prioritize STAT traffic over routine items

Prevent collisions and manage carrier queues

Provide tracking and reporting (who sent what, when, and where)

Integrate with hospital systems (like LIS, HIS) for better traceability

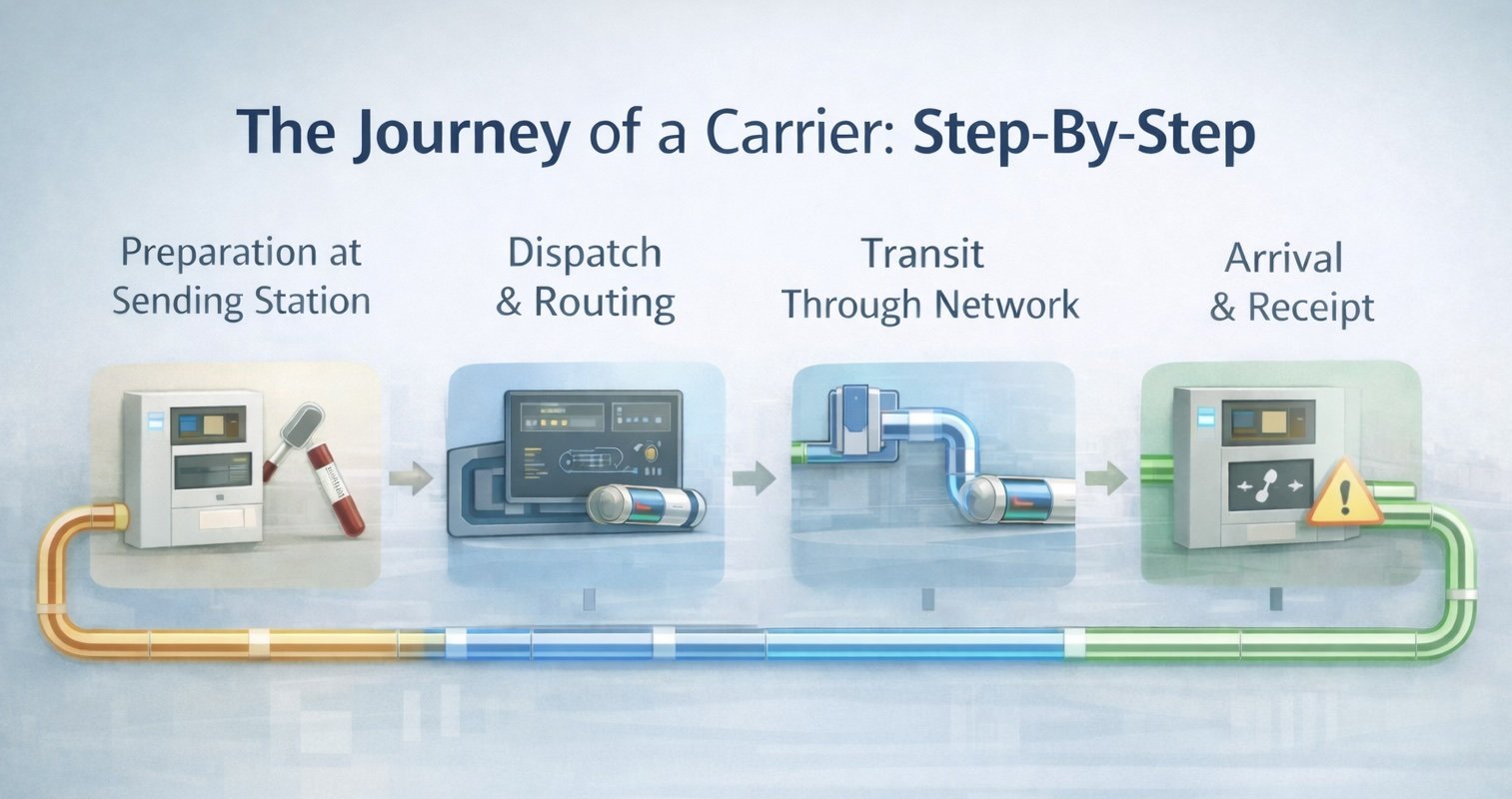

The Journey of a Carrier: Step-By-Step

Understanding the actual journey of a carrier helps leaders see where time is gained or lost.

Step 1 – Preparation at the Sending Station

Staff prepares the item (labels a blood tube, verifies patient info). The item is placed into a carrier with appropriate cushioning/packaging. The correct destination hospital tube station is selected using presets or manual entry.

Common failure modes here (and how good systems help):

Incorrect destination → mitigated by presets and department-based routing

Poor packaging → mitigated by standardized carriers and inserts

Mislabeling → mitigated by integrated barcode scanning at stations

Step 2 – Dispatch and Routing

Once dispatched:

The station notifies the central controller. The controller selects the best route based on network topology, current traffic, and item priority. Blowers create the necessary push/pull to move the carrier through the tubes.

For emergency or STAT items, the controller may reserve a "green lane" route, temporarily block non-STAT traffic on key segments, or log priority events for later reporting.

In one 400-bed facility we reviewed, giving STAT lab traffic formal routing priority reduced average STAT transport time by about 40% without adding any new stations. Purely through smarter routing rules.

Step 3 – Transit Through the Network

In transit, the carrier moves through straight runs and bends at controlled speeds, passes through diverters that switch it onto the correct branch, and can be re-routed on the fly if a station is busy or down.

What operations leaders should watch for: A good tube system hospital design minimizes sharp bends and long detours between key points, single-points-of-failure (like one riser that everything depends on), and congestion at "hub" nodes during peak periods.

Step 4 – Arrival & Receipt

Upon arrival at the destination station, the station signals staff (visual plus audible alerts). Staff retrieve the carrier, remove the contents, and confirm receipt. For integrated systems, receipt can update tracking records automatically.

At this stage, consistency matters more than raw speed. A 90-second trip is only useful if items don't sit unattended for 15 minutes. Training and clear ownership (which role empties stations, how often) are both important.

How Tube System Design Impacts Turnaround Time and Staffing

To most non-technical stakeholders, "we have a pneumatic tube system" sounds binary. Either you have one or you don't. But design quality separates a mediocre network from a real advantage.

Station Placement and Department Coverage

Questions operations leaders should be asking:

Do all high-volume specimen collection points have convenient stations?

Are stations in places where nurses naturally pass, without extra steps?

Are pharmacy, ED, OR, ICU, and the main lab connected on direct routes?

In several retrofit projects, simply adding or relocating a handful of stations on high-volume wards has increased tube utilization by 20–30%, because staff no longer need to go out of their way to use the system.

Routing, Zoning, and Priority Rules

Well-designed systems group stations into logical zones (lab cluster, ward cluster, surgery cluster), provide multiple pathways between zones to avoid bottlenecks, and use priority rules (like STAT lab specimens and emergency meds) that reflect clinical risk instead of just "first come, first served."

As an operations leader, you should be able to see average and 95th-percentile travel times between key pairs of stations, volume and congestion patterns during peak hours, and STAT vs routine traffic ratios and performance.

Integration with Workflows and Systems

Tube systems deliver their full value when they're integrated, not installed as a standalone gadget.

Examples:

Barcode scanning at tube stations that links specimens to LIS orders

Standardized packaging protocols agreed between lab, nursing, and pharmacy

SOPs that define when to use the system vs when to hand-carry items

Without that integration, your pneumatic transport system in hospitals becomes helpful but underutilized.

What Separates High-Performing Tube Systems

In our work designing and retrofitting hospital tube systems, we've found three decisions that consistently separate high-performing networks from average ones:

Designing for clinical pathways, not floor plans alone Start with your most time-sensitive flows (ED to Lab, OR to Lab, Pharmacy to ICU) and design routes around those, not around architectural convenience.

Making priorities visible in the software and the SOPs It's not enough to say "STAT is important." Priority has to be encoded in routing rules, reporting, and staff expectations.

Connecting physical movement with digital visibility When stations, LIS/HIS, and automation talk to each other, you get traceability and actionable data, not only faster tubes.

When these three elements align, we routinely see specimen transport times cut in half on key routes, with measurable improvements in lab TAT and staff satisfaction.

Common Concerns About Hospital Tube Systems (and How to Address Them)

Operations leaders typically hear a few recurring worries from clinical teams.

"Will This Damage Blood Samples or Medications?"

Modern hospital-grade systems are engineered to transport specimens safely when the right routes and speed profiles are used, carriers and inserts are designed for the payload, and the system and workflows are validated collaboratively with the lab and pharmacy.

Validation studies and pre-analytical guidelines can be built into your implementation plan so clinical leaders see data, not promises.

"What Happens When the System Goes Down?"

Resilient designs include redundant blowers and key risers, alternate routing options when individual stations are offline, and clear downtime procedures (who carries what, where, and how).

Your maintenance and service model should be part of the business case, not an afterthought.

"Will Staff Actually Use It?"

Adoption depends on intuitive station interfaces and location, training aligned to real-world workflows (not lectures alone), and demonstrable time savings for frontline staff, not leadership ROI slides alone.

Pilots, shadowing, and feedback loops during rollout can dramatically increase utilization.

What Operations Leaders Should Look for in a Hospital Tube System

When you evaluate a new or upgraded pneumatic tube system hospital, consider:

Clinical coverage: Are all key pathways (ED–Lab, OR–Lab, Pharmacy–ICU, etc.) directly connected?

Performance: Can the system meet your peak volume without bottlenecks?

Reliability: What uptime, redundancy, and service levels are realistic in your environment?

Scalability: Can you add new stations or zones as your facility grows or reconfigures?

Data & reporting: Can you track travel times, priorities, and usage patterns to support continuous improvement?

A tube system is infrastructure. Designed well, it becomes part of the hospital's nervous system.

Key Takeaways for Operations Leaders

A hospital tube system is a network of stations, carriers, tubes, and controllers. Not tubes in the ceiling alone.

Design decisions about coverage, routing, and priorities have a direct effect on lab TAT, staff workload, and patient flow.

Integration with LIS/HIS, lab automation, and clear SOPs is where you get the full value of the system.

The difference between an average and a high-performing system often comes down to how well it reflects your real clinical workflows.

Next Step: Get a Hospital Tube System Readiness Review

Ready to see how your tube system is really performing for your teams?

Schedule a Support Consultation and we’ll review your current setup, challenges, and goals—and suggest practical ways to get more from the infrastructure you already have.

Frequently Asked Questions About Hospital Tube Systems

How fast is a hospital tube system?

Most hospital-grade pneumatic tube systems can deliver carriers between connected departments in 60–120 seconds, depending on distance and routing. The real advantage is consistency: you can design for predictable transport times even during busy periods.

Are pneumatic tube systems safe for blood samples?

Yes, when designed and validated correctly. Modern systems use speed profiles, carrier inserts, and route selection to protect sensitive specimens. Labs should always validate tube transport for specific tests and specimen types before going live.

What can you send through a hospital tube system?

Common payloads include blood and other lab specimens, documents, small supplies, and certain medications. Each hospital sets its own rules based on pharmacy, lab, and infection prevention guidelines.