Pneumatic Tube Systems in Hospitals: Design Best Practices for 24/7 Reliability

In many hospitals, the pneumatic tube system is invisible. Until it isn't.

When it's working, specimens, medications, and documents quietly move between departments in under a minute. When it isn't, phones light up, porters scramble, and clinicians start asking why their STAT results are late.

If you're planning a new network or evaluating an existing one, design is the single biggest lever you have for long-term performance. Hardware matters, but how that hardware is laid out, configured, and governed will determine whether your system runs smoothly at 2 p.m. Monday and 3 a.m. Sunday, or becomes a chronic frustration.

This guide focuses on design best practices for pneumatic tube systems in hospitals, with a practical lens for operations leaders, facilities teams, and lab/pharmacy stakeholders who need 24/7 reliability.

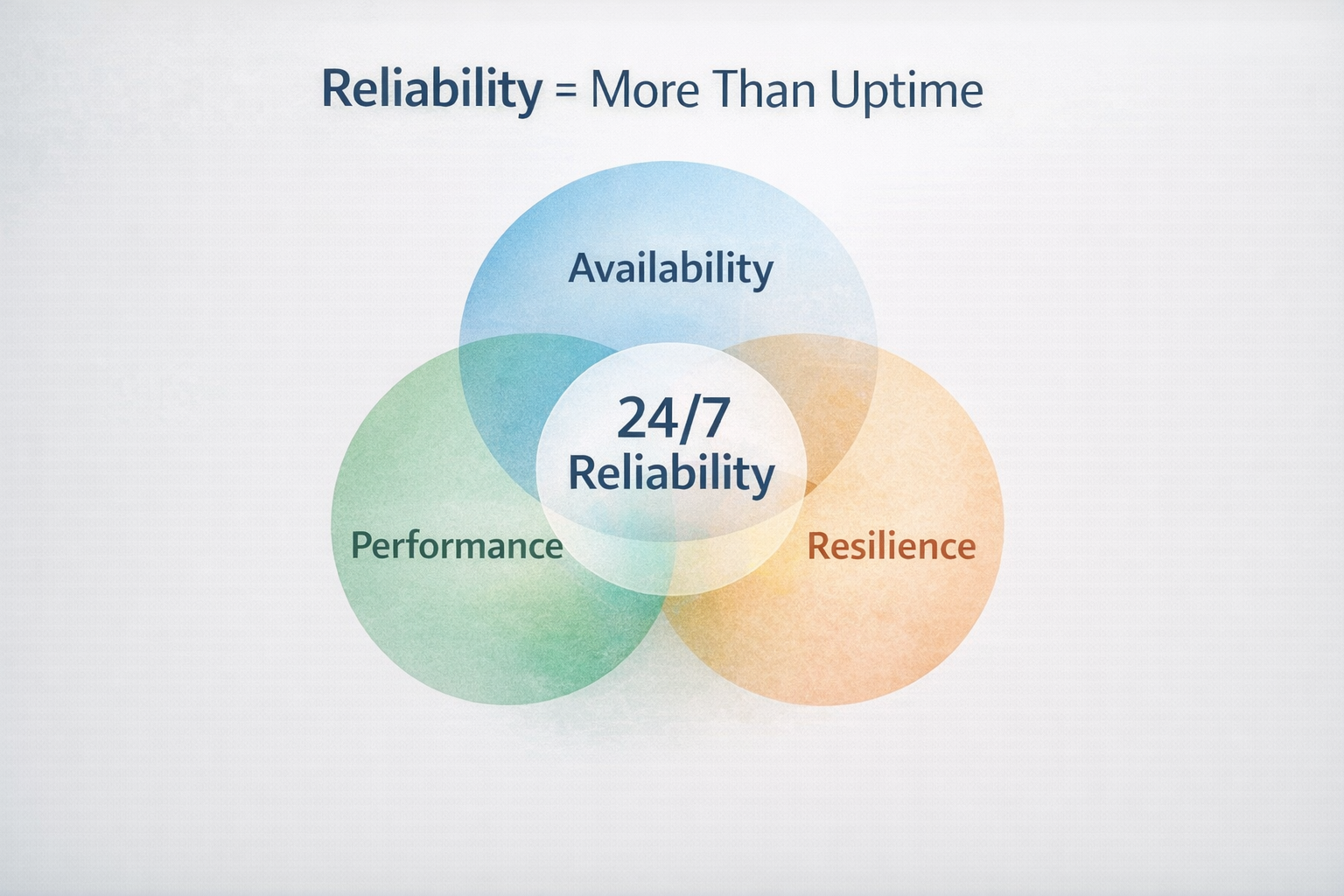

What "24/7 Reliability" Really Means in a Hospital

Before we get into layouts and routing, it's worth defining what reliability actually looks like from an operational standpoint.

For most hospitals, a reliable pneumatic tube system hospital should be able to:

Handle peak volumes without noticeable slowdowns

Deliver predictable transport times between key locations

Prioritize STAT and emergency items without disrupting routine traffic

Fail gracefully when components are offline (with clear fallbacks)

Be maintainable without major operational disruption

Reliability is the combination of availability, performance, and resilience under real clinical pressure.

Start with Clinical Pathways, Not Just Floor Plans

Most tube systems are drawn on architectural plans, but they're ultimately judged by clinical outcomes: turnaround time, staff time, and patient flow.

Map Your Most Critical Transport Flows

Before committing to a network layout, map your most important pathways:

ED ↔ Central Lab

OR ↔ Lab / Blood Bank

ICU / Critical Care ↔ Lab

Pharmacy ↔ ED / ICU / Wards

For each pair, ask:

How many items move per day (and at what times)?

What's the acceptable transport time for STAT vs routine items?

What happens today when things are delayed?

Many facilities we've worked with see a small number of routes account for a disproportionate share of clinical risk. Designing those routes as "express lanes" inside your tube system hospital is often the highest-ROI decision you'll make.

Design the Network Around Those Flows

Once you've identified priority pairs:

Place hospital tube stations as close as practical to actual workflows (near phlebotomy draw areas or nursing work areas, not just "somewhere on the ward").

Minimize hops and detours between your key pairs, even if it means slightly longer routes for low-risk traffic.

Use risers and trunk lines to create direct, high-capacity connections between important clusters (ED–Lab–OR).

The goal is not a perfectly symmetrical network. It's a network biased toward the clinical pathways that matter most.

Best Practices for Station Placement and Coverage

Stations are where staff interact with the system. Poor placement is one of the most common reasons a tube network underperforms.

Put Stations Where Work Actually Happens

When planning station locations:

Follow the workflow:

Phlebotomy and specimen collection areas

Nursing stations and medication rooms

OR core / anesthesia work areas

Pharmacy dispensing points

Central receiving in the lab

Avoid locations that require extra steps or access badges just to use the system. Consider visibility. If staff can't see the station, they're less likely to use it regularly.

We routinely see utilization jump 20–30% when stations are relocated from "convenient for the building" locations to "convenient for the user" locations.

Balance Enough Stations vs. Too Many

More stations are not always better.

Too few stations force staff to walk long distances, so they default back to porters or hand-carry. Too many stations can increase complexity, cost, and potential failure points.

The right approach:

Make sure every major clinical unit that frequently sends or receives items has at least one well-placed station.

For high-volume units (ED, central lab, blood bank), consider dedicated STAT stations to isolate time-sensitive flows from routine traffic.

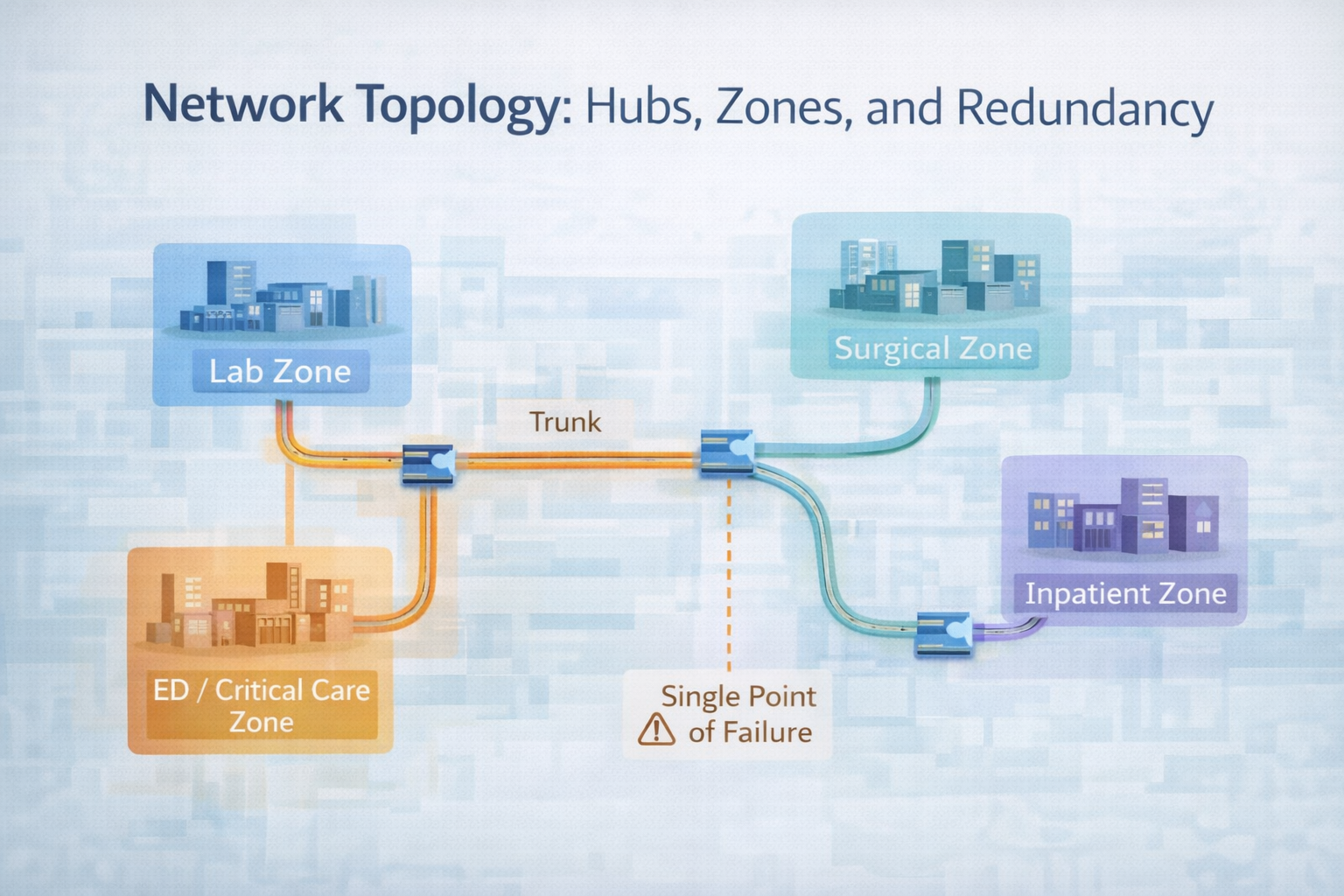

Network Topology: Hubs, Zones, and Redundancy

The topology (the way tubes connect stations) is where much of the reliability is won or lost in pneumatic tube systems in hospitals.

Use Zones to Localize Traffic

A common best practice is to divide the network into logical zones:

Lab zone: lab, blood bank, related support areas

Emergency / Critical Care zone: ED, ICU, step-down units

Surgical zone: OR, pre-op, PACU

Inpatient ward zone(s): med-surg, specialty units

Within each zone, stations communicate primarily with a small number of key endpoints. Internal traffic stays local when possible, reducing load on central trunks.

Zoning helps you:

Contain the impact of a failure or maintenance event

Reduce congestion on main trunks

Prioritize traffic between zones more intelligently in the controller

Design Hubs and Trunks with Redundancy in Mind

Most networks use trunks and hubs to connect zones:

Trunk lines: high-capacity, often vertical shafts that connect floors or major areas.

Hubs / transfer units: where carriers are routed between trunks and zone branches.

What works:

Avoid single-point-of-failure trunks that all traffic must use. Where possible, design at least two trunk paths between key zones.

Make sure hubs and important risers have redundancy in blowers or paths, so the system can reroute around a failed component.

For extremely high-risk routes (OR to blood bank), consider independent or partially independent loops that can operate even if other zones are degraded.

Routing Logic and Priority Rules

Hardware moves the carriers. Software decides how, and for whom.

Encode Clinical Priorities in the System

Your pneumatic tube system hospital controller can typically:

Assign priority levels to different item types (STAT lab, blood products, emergency meds, routine samples).

Reserve capacity or dedicated lanes for specific priorities.

Throttle or defer low-priority traffic during peak times.

What works well:

Work with lab, pharmacy, and nursing to define clear priority categories (STAT vs urgent vs routine) and when each applies.

Configure controller rules to reflect those categories, not generic "high, medium, low" settings.

Periodically review travel time data by priority to confirm the system behaves the way you expect.

In one 500-bed hospital, we saw STAT specimens routinely trapped behind routine ward traffic at midday. Reconfiguring priority rules and reserving capacity on key trunks cut average STAT transport time by about 40% without adding new hardware.

Avoid "Traffic Jams" at Busy Nodes

Even with good priority rules, you can get congestion at heavily used hubs, the central lab station, or pharmacy stations during med rounds.

Use your controller's monitoring tools to identify stations or routes with frequent queues or delays, adjust routing or add alternate paths where justified, and consider staggered dispatch rules for non-critical traffic (batch routine samples when STAT volume is low).

Designing Pneumatic Transport Systems in Hospitals for Maintenance and Upgrades

A 24/7 hospital never fully "closes," but your system will still need service, upgrades, and repairs.

Plan for Maintainability from Day One

When designing or retrofitting your pneumatic transport system in hospitals:

Make sure key components (blowers, controllers, hubs) are physically accessible without major disruption.

Use standardized carriers and station types as much as possible to simplify spares and training.

Document the network thoroughly: as-built drawings, zone definitions, station IDs, and routing rules.

This reduces downtime when something does go wrong and lowers long-term maintenance cost.

Design for Incremental Expansion

Hospitals change. New wings open, services move, and bed counts grow.

Design choices that support expansion:

Leave capacity in main trunks for additional branches.

Include "future station" stubs in design and budget, even if they're not populated immediately.

Work with your vendor to validate how many additional stations or routes your current controllers and blowers can support before major upgrades.

Atreo's Design Principles for Reliable Hospital Tube Systems

Across Atreo projects, we've found a few principles that reliably improve performance and reduce surprises over time.

1. Design Around Real Data, Not Assumptions

Where possible, we start with:

Historic transport volumes (specimens, meds, documents)

Peak-time patterns (shift changes, morning draws, OR schedules)

Current turnaround times and "pain point" routes

This allows us to design a pneumatic tube system hospital that reflects how your hospital actually works, not how it looks on paper.

2. Co-Design with Clinical Stakeholders

We involve:

Lab and blood bank leaders (specimen safety, validation, TAT targets)

Pharmacy (medication policies, secure handling)

Nursing and unit managers (workflow fit, staffing impact)

This reduces resistance later and makes sure design decisions are clinically sound, not only technically appealing.

3. Build in Monitoring from Day One

We encourage hospitals to use controller data to track travel times, volumes, and error events, establish clear KPIs (average and 95th-percentile travel times for top 10 routes), and review performance periodically with clinical and operations teams.

In one multi-site system, building in monitoring and review helped identify a persistent routing issue between ED and lab that was adding 3–4 minutes to specimen journeys during certain hours. An issue that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

Common Design Pitfalls to Avoid

Even well-intentioned projects can run into avoidable problems.

Over-Optimizing for Construction Convenience

If tube routing is driven solely by minimizing construction cost, important routes may become longer and more complex than they need to be, and stations may end up in "leftover" spaces that are inconvenient for staff.

A better approach balances construction efficiency with clinical priorities.

Ignoring Validation and Item Policies

If lab and pharmacy policies aren't aligned with design, certain tubes or routes may not be approved for specific specimens or medications, and staff may mistrust the system and default to hand-carrying high-risk items.

Build validation and policy development into your design timeline, not as an afterthought.

Underestimating Change Management

Even the best-designed system will underperform if staff are not trained on when and how to use it, roles (who empties stations, who monitors queues) are unclear, or there's no feedback loop for issues and improvements.

Include training, communication, and governance in your project scope.

Key Takeaways for Designing Reliable Pneumatic Tube Systems

Design your pneumatic tube systems in hospitals around real clinical pathways, not floor plans alone.

Place stations where work actually happens, and size your network with zones and trunks that support your peak loads.

Encode clinical priorities into routing logic so STAT and high-risk items always move first.

Plan for maintenance and expansion from the start, with clear documentation and monitoring.

Co-design with clinical stakeholders to make sure the system is trusted, validated, and fully utilized.

Next Step: Schedule a Support Consultation

If you’re planning a new pneumatic tube system—or rethinking an existing one—the most effective next step is a focused conversation about your reality on the ground.

Schedule a Support Consultation

We’ll:

Review your current tube system setup and how it supports key departments

Discuss the reliability, performance, and workflow challenges you’re seeing

Connect your goals for TAT, staffing, and safety with what your existing system and partners can do

Outline practical options to get more from your network and plan for future needs

Frequently Asked Questions About Pneumatic Tube System Design

How many stations should a hospital pneumatic tube system have?

There's no one-size-fits-all number. The right count depends on bed numbers, building layout, and workflow. As a rule of thumb, every high-volume clinical unit that frequently sends or receives items should have at least one well-placed station, with additional stations in high-traffic or specialized areas like ED, OR, and the central lab.

Can an existing tube system be redesigned without replacing everything?

Often, yes. Many hospitals can significantly improve performance by adding or relocating key stations, adjusting routing logic and priority rules, or upgrading controllers or blowers in targeted segments. A full replacement is not always necessary to gain major reliability improvements.

How do we know if our current system is under-designed?

Warning signs include frequent complaints about slow or unreliable deliveries, nurses and porters regularly hand-carrying items instead of using stations, and significant differences between expected and actual travel times on key routes. A data-driven review of travel times, volumes, and routes usually reveals whether the issue is design, configuration, hardware, or workflows.