From Vein to Result: The End-to-End Journey of a Blood Sample in the Hospital

Every lab result starts the same way: with a patient, a vein, and a tube.

From there, the path gets more complex. A single blood sample collection may pass through multiple hands, systems, and spaces before its results appear in the electronic record. At each step, there are opportunities to protect or compromise turnaround time and quality.

For operations leaders and lab managers, understanding this end-to-end journey is essential. It makes clear where to invest, where to standardize, and where to automate.

We'll follow one blood sample through the hospital, from vein to result, and highlight the critical moments that shape speed, safety, and accuracy.

Step 1 – The Order: Setting the Journey in Motion

Every journey starts with a clinical question.

A physician, advanced practice provider, or protocol triggers lab orders in the EHR. Orders flow into the LIS and are queued for collection. Priority (STAT vs urgent vs routine) is set, explicitly or implicitly.

Incorrect or incomplete orders can lead to wrong tests being performed, extra draws, or confusion downstream. Priority decisions begin affecting eventual turnaround time (TAT).

What works:

Use standardized order sets where appropriate.

Make sure STAT criteria are clear so the label "urgent" reflects true clinical need, not habit.

Step 2 – Blood Collection at the Patient's Side

Now we reach the most familiar part of the blood test process: the draw.

Patient Identification and Preparation

At the bedside or in a phlebotomy chair, the collector confirms patient identity with at least two identifiers (name + date of birth or MRN). Patient positioning, site selection, and any necessary fasting or preparation are confirmed.

Errors here (wrong patient, wrong order) can't be fixed later. This is the first major control point.

Venipuncture and Tube Selection

During blood specimen collection:

The collector follows proper venipuncture technique, including site cleaning and tourniquet timing. Correct tubes (serum, EDTA, citrate, etc.) are chosen based on the ordered tests. The proper order of draw is followed to minimize cross-contamination of additives.

Tube choice and draw order directly influence pre-analytical quality and whether specimens will be acceptable for testing.

Immediate Labeling at the Point of Care

Immediately after draw:

Labels are printed (ideally at the bedside) from the LIS/EHR order. Tubes are labeled with barcodes and human-readable identifiers before leaving the patient. For transfusion-related testing, additional safety steps (second check or signature) may be required.

Bedside labeling ties the sample to the right patient and order, and sets up traceability for the rest of the journey.

Step 3 – Local Handling and Dispatch: The "Hidden Minutes"

Once the blood sample is collected and labeled, it leaves the patient, but it may not leave the unit immediately.

Here's what typically happens:

Tubes are placed in racks, trays, or small containers at the nursing station or phlebotomy area.

Staff decide whether to send immediately or wait to batch with other samples.

A choice is made between hand-carrying, porter pickup, or sending via pneumatic tube.

Many of the hidden minutes in TAT accumulate here:

Waiting for a porter who comes every 30–60 minutes

Samples sitting briefly (or not so briefly) on counters before being noticed

Unclear expectations about when to use the tube system vs manual transport

Even a 5–10 minute delay here, repeated across dozens or hundreds of samples, has a measurable impact on TAT and lab workload.

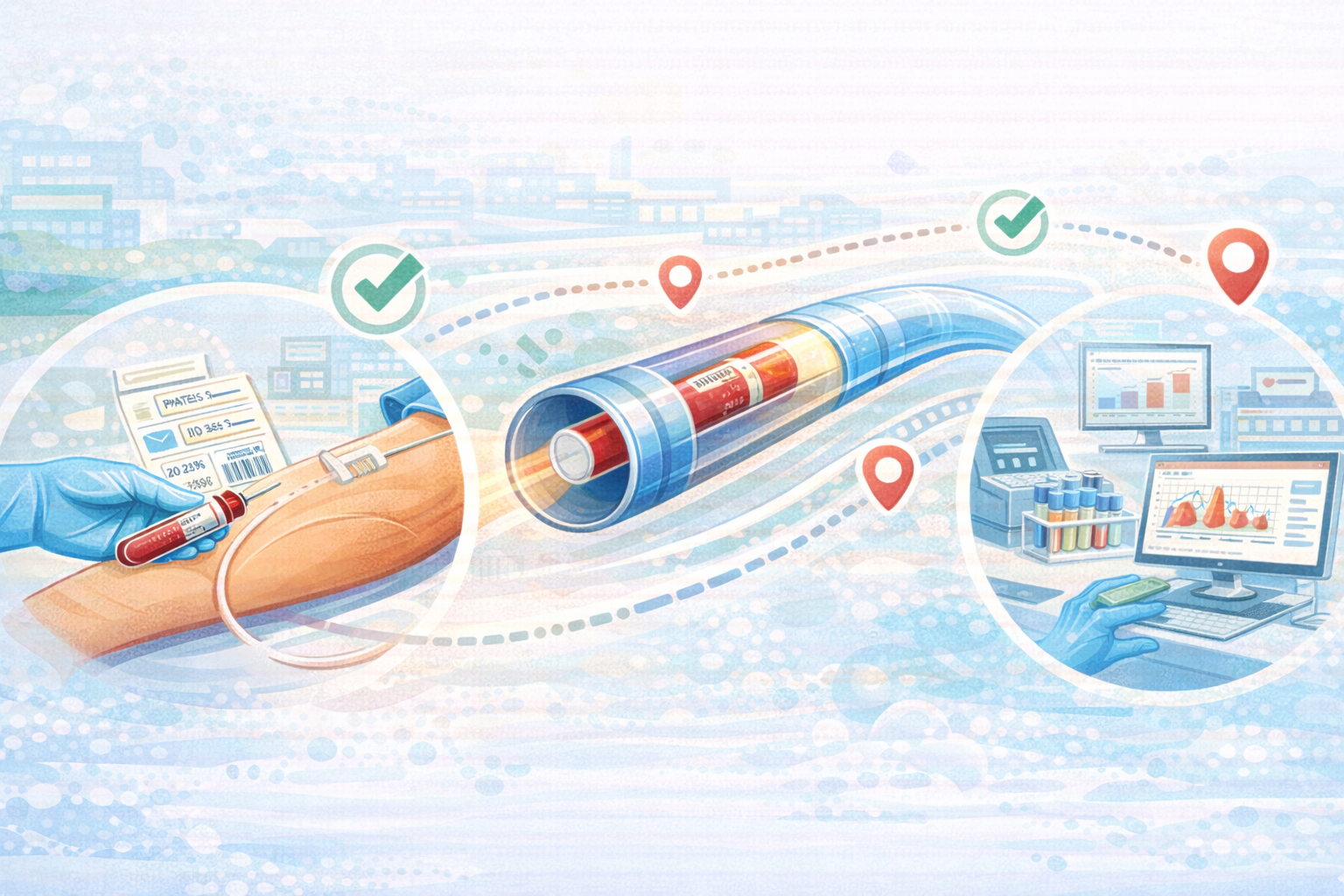

Step 4 – Transport: Getting the Sample to the Lab

Transport is the bridge between collection and analysis. The method your hospital uses (manual, scheduled courier, pneumatic tube) shapes both speed and variability.

Manual Walk or Porter Route

In many hospitals:

Nurses or aides walk specimens to the lab when time allows. Porters follow scheduled routes, stopping at units to collect samples.

Strengths:

Simple, low-tech, and flexible.

Risks:

Highly variable timing (staff availability, distance, elevator waits).

Little traceability if something goes missing.

Hidden labor cost for clinical staff.

Pneumatic Tube System

In hospitals with a tube network:

Samples are placed in carriers with appropriate inserts. Staff select the lab station on the interface and dispatch the carrier. Carriers travel at controlled speeds through the tube network, often arriving in 60–90 seconds for common routes.

Strengths:

Fast and more consistent transport times.

Frees clinical staff from acting as couriers.

Risks (if not validated and managed correctly):

Mechanical stress contributing to hemolysis if routes and speeds are poorly configured.

Misuse if specimens that shouldn't be tubed are sent anyway.

Step 5 – Lab Receipt and Accessioning

The next leg of the journey happens inside the lab.

Specimen Receipt and Check-In

At the lab's receiving area:

Specimens are removed from racks or carriers. Barcodes are scanned and arrival times are logged in the LIS. Technologists verify labeling and specimen integrity (volume, clots, leaks, hemolysis, etc.).

What matters here:

Clear criteria for accepting vs rejecting specimens

Fast, consistent receipt workflows, especially for STAT samples

The ability to distinguish transport-related issues from collection issues

Prioritization and Routing Inside the Lab

Once accessioned, specimens are sorted by test panel and priority (STAT vs routine), routed to appropriate pre-analytical stations (centrifugation, aliquoting, etc.), and directed toward analyzers or manual benches.

Automated lab systems can streamline this routing, but they rely on the timing and consistency of incoming specimens to run optimally.

Step 6 – Pre-Analytical Processing

Before analysis, most blood samples undergo pre-analytical preparation:

Centrifugation for serum or plasma

Aliquoting into secondary tubes as needed

Storage under controlled temperature conditions if immediate analysis is not possible

This stage is sensitive to:

Time since collection and arrival

Temperature control and handling

Any damage or hemolysis introduced during collection or transport

Strong pre-analytical processes protect sample integrity, minimize reject/recollect rates, and provide a stable foundation for accurate test results.

Step 7 – Analysis: From Sample to Result

Now the sample finally meets the analyzer.

Running the Tests

Depending on the requested tests:

Samples are loaded onto automated analyzers (chemistry, hematology, immunoassay, etc.). Certain specialized tests may be performed on dedicated instruments or via manual methods. Quality controls and calibration are run according to schedule and regulations.

Automation can process large volumes quickly, but its efficiency still depends on:

Steady, appropriately prioritized specimen flow

Minimal interruptions from invalid or rejected samples

Good alignment between test demand and analyzer capacity

Verification and Result Release

After analysis:

Results are checked against control limits and critical value thresholds. Technologists review and verify results, especially for critical or unusual findings. Verified results are released to the LIS/EHR, where clinicians can view them.

The journey from vein to result ends here, but the clinical decision-making journey is just beginning.

Step 8 – Turnaround Time and the Patient Experience

From a patient's perspective, the blood draw is the visible moment. From a hospital's perspective, turnaround time for blood samples is often the KPI that gets tracked.

What to remember:

Every step described above (ordering, collection, labeling, local handling, transport, receipt, pre-analytics, analysis) adds time and risk.

Fixating only on analyzer speed misses major improvement opportunities upstream.

Small improvements in early steps (dispatching samples faster, using validated tube routes) can have compounding benefits all the way through.

When the system works well:

Clinicians trust that "STAT" really means fast, reliable TAT.

Patients spend less time waiting anxiously for results.

Labs and operations teams spend more time on value-added work and less on chasing missing specimens or resolving avoidable errors.

Where the Journey Breaks, and How to Fix It

Following the journey makes it easier to see where things go wrong.

Common breakpoints:

At order and collection: incorrect tests, wrong patient, poor collection technique.

At local handling: samples sitting un-dispatched, unclear responsibilities.

In transport: slow manual methods, no use of tube systems where validated, or misuse of tubes where they aren't validated.

At receipt: inconsistent accessioning, unclear STAT handling.

In pre-analytics: delays in centrifugation or processing due to uneven sample arrival.

Improvements typically come from:

Standardizing workflows at each step

Clarifying roles and handoffs

Aligning transport design (including pneumatic tube systems) with real clinical pathways

Using data (TAT reports, hemolysis indices, rejection rates) to guide changes

Atreo's Lens on the Blood Sample Journey

Atreo looks at the blood collection and analysis journey as an integrated system, not a set of isolated tasks.

What that means:

Mapping real routes and times from bedside to bench, not only lab processing times.

Designing transport solutions (manual, courier, pneumatic tube) that match specimen flows and clinical priorities.

Supporting hospitals in validating and monitoring these systems so that speed doesn't come at the expense of safety.

When all the links in the chain are visible, hospitals can move beyond "the lab is too slow" to specific, fixable changes at the bedside, in transport, and inside the lab.

Key Takeaways from Vein to Result

A blood sample's journey spans multiple departments and systems. TAT is the sum of many small intervals.

Early steps (ordering, identification, bedside labeling, dispatch choice) have outsized influence on speed and quality.

Transport is a major, often under-managed part of the blood sample journey, not simply "what happens between collection and lab."

Pre-analytical processes in the lab rely on predictable, timely specimen arrival to function optimally.

Seeing the full chain enables better decisions about where to invest (workflow, staffing, tube systems, automation) to improve both TAT and safety.

Next Step: Talk with Atreo

If you want to understand where time and risk are really hiding in your blood sample journey, our team can help.

Review how blood samples currently move from vein to result across key units

Identify major delays and risk points in your existing workflows and transport

Discuss practical changes that could improve TAT and pre‑analytical quality

Frequently Asked Questions About the Blood Sample Journey

Where is most time lost between vein and result?

It varies, but in many hospitals, a large share of delay occurs between collection and lab receipt (in local handling and transport) rather than on the analyzers themselves.

Does using a pneumatic tube system always speed up the journey?

It often does for validated specimen types and well-designed routes. However, speed gains depend on proper system design, route selection, and clear policies about what can safely be sent via tube.

How can we start improving without a big technology project?

Begin by mapping and measuring how long samples spend on the unit before dispatch, how they are currently transported, and how long it takes from collection to lab receipt on key routes. You can often see tangible TAT improvements by clarifying policies, changing dispatch habits, and tightening handoffs before adding new hardware.