Building a Lean Hospital Transport System: From Porters to Pneumatic Tubes

Every hospital runs on movement.

Specimens, medications, blood products, documents, equipment, and supplies all need to get from point A to point B. Often quickly, always safely. Yet in many organizations, internal transport is still a patchwork of ad-hoc porter runs, nurses "just walking things over," and underused automation.

The result: wasted staff time, unpredictable turnaround times, and avoidable delays in care.

A lean hospital transport system treats internal movement as a designed process, not a background chore. It uses the right mix of people and technology (porters, standardized routes, and pneumatic tubes) to reduce waste and free staff to focus on patient care.

This article outlines how operations leaders can move from reactive transport to a lean, reliable system.

What "Lean" Means in Hospital Transport

Lean thinking isn't new in healthcare, but it's often applied to clinical workflows more than logistics. For transport, lean means:

Eliminating waste (unnecessary motion, waiting, overprocessing)

Creating flow (smooth, predictable movement of items)

Pulling work based on demand, not arbitrary schedules

Making problems visible so they can be fixed quickly

In a lean hospital transport system, you should be able to answer:

What's moving, how often, and by whom?

Where are delays and bottlenecks?

How much staff time is tied up in movement vs direct care?

The Current State: How Hospitals Usually Move Things

Most hospitals rely on a mix of:

Nurses and clinical staff acting as ad-hoc couriers

Porters/transporters in hospitals with scheduled or on-demand tasks

Pneumatic transport (pneumatic tube systems) in some areas

Vehicle couriers between campuses or to reference labs

But without a designed system:

Responsibilities blur ("If no one's free, the nurse just brings it.")

Routes and frequencies are based on habit, not data

Automation may be underused or misused

No one "owns" end-to-end transport performance

The opportunity is to design a system where every movement has a purpose and a plan.

Step 1 – Map What You're Moving and Why

You can't make transport lean until you see it clearly.

Inventory Transport Flows

Start with a simple inventory of what moves inside your hospital:

Lab specimens

Blood products and blood samples

Medications (routine and STAT)

Documents (consents, charts, legal forms)

Supplies and equipment (IV pumps, portable monitors, devices)

For each category, ask:

Where does it originate and where does it go?

How often does it move (per shift/day)?

Who typically moves it (nurse, porter, courier, pneumatic tube)?

How time-sensitive is it?

Even a basic spreadsheet or whiteboard exercise will reveal:

High-volume, high-risk flows (ED ↔ Lab, OR ↔ Blood Bank, Pharmacy ↔ ICU)

Low-volume, flexible flows (nonurgent supplies, routine documents)

Where clinical staff are acting as unpaid logistics workers

Step 2 – Identify the Seven Wastes in Hospital Transport

Lean frameworks describe seven types of waste (plus an eighth: underused talent). All of them show up in transport.

Motion

Unnecessary movement of people and items:

Nurses walking specimens to the lab multiple times per shift

Porters "wandering" between units instead of following optimized routes

Waiting

Time when patients, staff, or processes are idle:

Samples waiting in racks for the next porter run

Medications delayed because transport wasn't available

Equipment not available when needed because it's in transit

Transportation (Poorly Designed)

Ironically, transport itself can be a waste when items are moved multiple times or via indirect routes, or tasks are duplicated (porter and nurse both moving items to the same place).

Overprocessing

Extra work that doesn't add value:

Excessive handoffs between staff

Manual logging or tracking that could be automated

Overproduction

Moving or preparing more than needed at a time. Oversized batches of specimens or supplies sent "just in case," leading to crowding and delays downstream.

Defects

Errors that require rework:

Lost or mislabeled specimens

Damaged items in transit

Misdelivered medications or blood products

Inventory

Too much or too little on hand:

Units hoarding supplies because they don't trust the transport system

Empty stock due to slow or unpredictable resupply, leading to last-minute rushes

Recognizing these wastes gives you a checklist to improve against.

Step 3 – Design a Tiered Transport Strategy

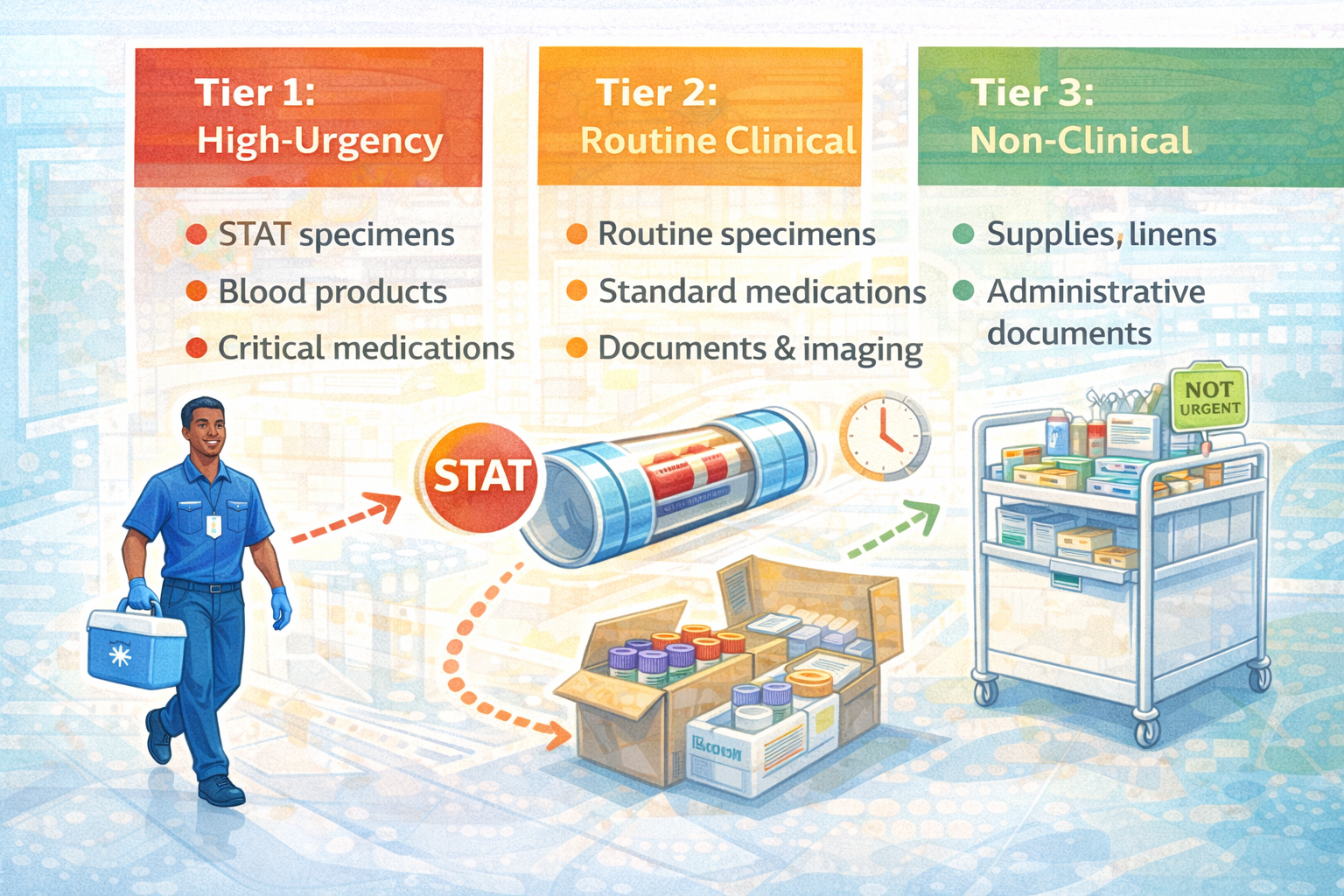

A lean hospital transport system doesn't use one method for everything. It deliberately matches item type + urgency, distance + frequency, and risk + value to the right combination of porters, routes, and automation.

Tier 1 – High-Urgency, High-Risk Items

Examples:

STAT lab specimens from ED, ICU, OR

Blood products for active transfusions

Critical medications (thrombolytics, vasopressors)

What works:

Use validated pneumatic tube routes wherever possible for speed and consistency.

Where tube use is not validated or allowed (certain blood products), use clearly defined, fast manual courier paths with dedicated staff.

Encode priorities in both the pneumatic tube system hospital controller and porter workflows. STAT must mean something operationally.

Tier 2 – Routine Clinical Items

Examples:

Routine lab specimens

Standard medication runs

Non-urgent imaging films or documents

What works:

Use a mix of pneumatic tube (for validated specimens) and well-scheduled porter routes.

Avoid ad-hoc "whoever is free" decisions. They create variability and waste.

Optimize porter routes and frequencies based on actual demand, not tradition.

Tier 3 – Non-Clinical or Low-Urgency Items

Examples:

Supplies, linens, non-urgent equipment

Administrative documents not tied to immediate care

What works:

Use scheduled porter routes or materials management processes.

Separate these flows from time-sensitive clinical transport so they don't compete for capacity.

Step 4 – Optimize Human Transport: Porters and Staff

Even with advanced automation, human transport isn't going away. The goal is to make it focused and efficient, not casual and invisible.

Clarify Roles and Ownership

Decide and document:

What do nurses move vs what do porters move?

Under what conditions does a nurse hand-carry (system down, ultra-critical)?

Who is responsible for emptying tube stations and when?

Clarity reduces "everyone and no one" responsibility.

Standardize Porter Routes and Tasks

Rather than loosely defined "coverage," design specific routes (Lab–ED–ICU–Step-down–Lab) with defined frequencies. Use demand data (task volume by hour) to adjust schedules. Consider splitting roles: some porters focus on patients, others on tube transport overflow and item movement.

Use simple visual tools (route maps, schedules, task boards) to keep work visible.

Step 5 – Get the Most from Pneumatic Transport

Pneumatic tubes are often the backbone of a lean internal logistics system, but only when they're designed and used intentionally.

Design Around Clinical Pathways

As covered in your design article:

Build direct, high-capacity routes between ED, OR, ICU, and lab.

Place stations where staff actually work, not where space happens to exist.

Use zones and redundancy to prevent bottlenecks.

Validate and Communicate What's Safe to Send

To protect pre-analytical quality and patient safety:

Validate routes and speeds for relevant specimens (routine blood samples).

Define and publish a list of acceptable and restricted items for tube transport.

Train staff on when to tube vs when to walk.

Monitor Use and Performance

Use system data to:

Track volumes and travel times by route and time of day.

Identify congestion points or underused stations.

Adjust routing logic, priorities, or station locations as needed.

Lean is iterative. The data from your pneumatic transport network is a goldmine for continuous improvement.

Step 6 – Make Flow and Problems Visible

Lean systems thrive on visibility. People need to see what's moving, where it's stuck, and what's changing.

Dashboards and Simple Metrics

Consider tracking and sharing:

Average and 95th-percentile transport times for key routes (ED↔Lab, OR↔Blood Bank, Pharmacy↔ICU)

Volume of items moved by porters vs pneumatic tube vs other methods

Percentage of specimens or items that meet defined time targets

Incident counts (lost items, delayed deliveries, hemolysis related to transport)

Even a simple monthly or quarterly dashboard helps align teams and justify changes.

Visual Controls on the Units

On units and in the lab:

Post quick guides for which items to tube vs walk.

Use color-coding or icons on carriers, bags, and containers.

Make tube station status visible (when stations should be emptied, who is responsible).

Small, visible cues reduce variation in daily practice.

Atreo's Role in Lean Hospital Transport

Atreo helps hospitals build lean, resilient transport systems that integrate human movement (porters, nurses, couriers), pneumatic tube systems (design, validation, routing, monitoring), and laboratory and pharmacy workflows (TAT, pre-analytical quality, med delivery).

What that means:

Mapping existing flows and identifying waste with operations and clinical leaders

Designing or refining tube networks to match real transport demand

Supporting validation and policy work so staff trust the system and use it correctly

Providing ongoing insight from system data to guide continuous improvement

When transport becomes a designed system instead of a background chore, hospitals see gains in TAT, staff satisfaction, and cost efficiency.

Key Takeaways for Building a Lean Transport System

Internal transport is a core part of lean hospital operations.

Nurses and clinicians should spend more time on care and less time acting as couriers.

A tiered strategy uses the right mix of porters, scheduled routes, and pneumatic tubes based on urgency and risk.

Validated, well-designed pneumatic tube systems are often the fastest and most consistent option for many clinical flows.

Visibility (through mapping, metrics, and clear roles) is essential to finding and eliminating waste.

Next Step: Talk with Atreo About Your Transport System

If you’re seeing delayed specimens, meds, or blood products—or nurses spending too much time walking items around the hospital—our team can help you think through a better approach.

Review how items currently move across key routes and departments

Identify patterns of waste, delay, and underused pneumatic transport

Discuss practical options for a leaner, more reliable hospital transport system

Frequently Asked Questions About Lean Hospital Transport

Will a lean transport system mean fewer porters?

Not necessarily. The goal is to use porters more effectively. In many cases, you reallocate effort from random, ad-hoc runs to focused, high-value routes that support clinical care.

Can we build a lean transport system without a pneumatic tube network?

You can make significant improvements with better routing, roles, and scheduling alone. However, for medium and large hospitals, validated pneumatic tube system hospital networks often become a key part of sustaining fast, predictable internal logistics.

Where should we start if we're resource-constrained?

Begin with mapping and measurement. Identify your top 5–10 critical routes (ED↔Lab, OR↔Blood Bank, etc.), measure current transport times and who is doing the work, and pilot a small number of changes (using the tube for specific STAT flows, adjusting porter routes) and track impact. Lean progress is incremental. You don't need a massive project to see meaningful gains.