Transporters in Hospitals: Who Owns the Journey of Critical Items?

In most hospitals, everyone assumes someone else is moving critical items.

Nurses assume porters will pick up specimens soon. Porters assume nurses will walk especially urgent items down. The lab assumes the pneumatic tube system will cover most flows. Pharmacy assumes "someone" will get meds where they need to go.

When no one clearly owns the journey, patients wait, staff get frustrated, and critical workflows depend on luck more than design.

This article looks at transporters in hospitals broadly (people, systems, and processes) and asks a simple question: who actually owns the journey of critical items? Then it offers a practical blueprint for clarifying roles, improving reliability, and freeing clinical staff from acting as ad-hoc couriers.

The Problem: Everyone and No One Is Responsible

Internal transport in many hospitals has grown organically:

A few porters were hired when the building expanded.

A pneumatic tube system was installed years ago.

Nurses "help out" by walking items when things get busy.

The result is a hazy division of labor. On some units, nurses regularly walk specimens to the lab. On others, porters handle nearly everything. Some staff trust the tube system. Others avoid it.

Symptoms you may recognize:

Inconsistent turnaround times between similar units

Frequent questions like "Did anyone send that sample?" or "Where's that blood product?"

Nurses and techs leaving patient care areas to ferry items around the hospital

You have motion and waiting waste, hidden labor costs, and avoidable risk, all because ownership isn't clear.

Who Are the "Transporters" in Your Hospital?

When we talk about transporters in hospitals, we're talking about more than people with "Transport" in their job title.

Most hospitals rely on a mix of:

Clinical staff: nurses, aides, phlebotomists, OR techs who hand-carry items when needed.

Porters / logistics staff: dedicated staff who move patients, specimens, meds, equipment, and supplies.

Pneumatic tube systems: automation that moves specimens, meds, and documents via carriers.

Vehicle couriers: moving items between buildings or campuses.

All of these are transporters in a functional sense. A lean, safe system recognizes that and assigns explicit roles.

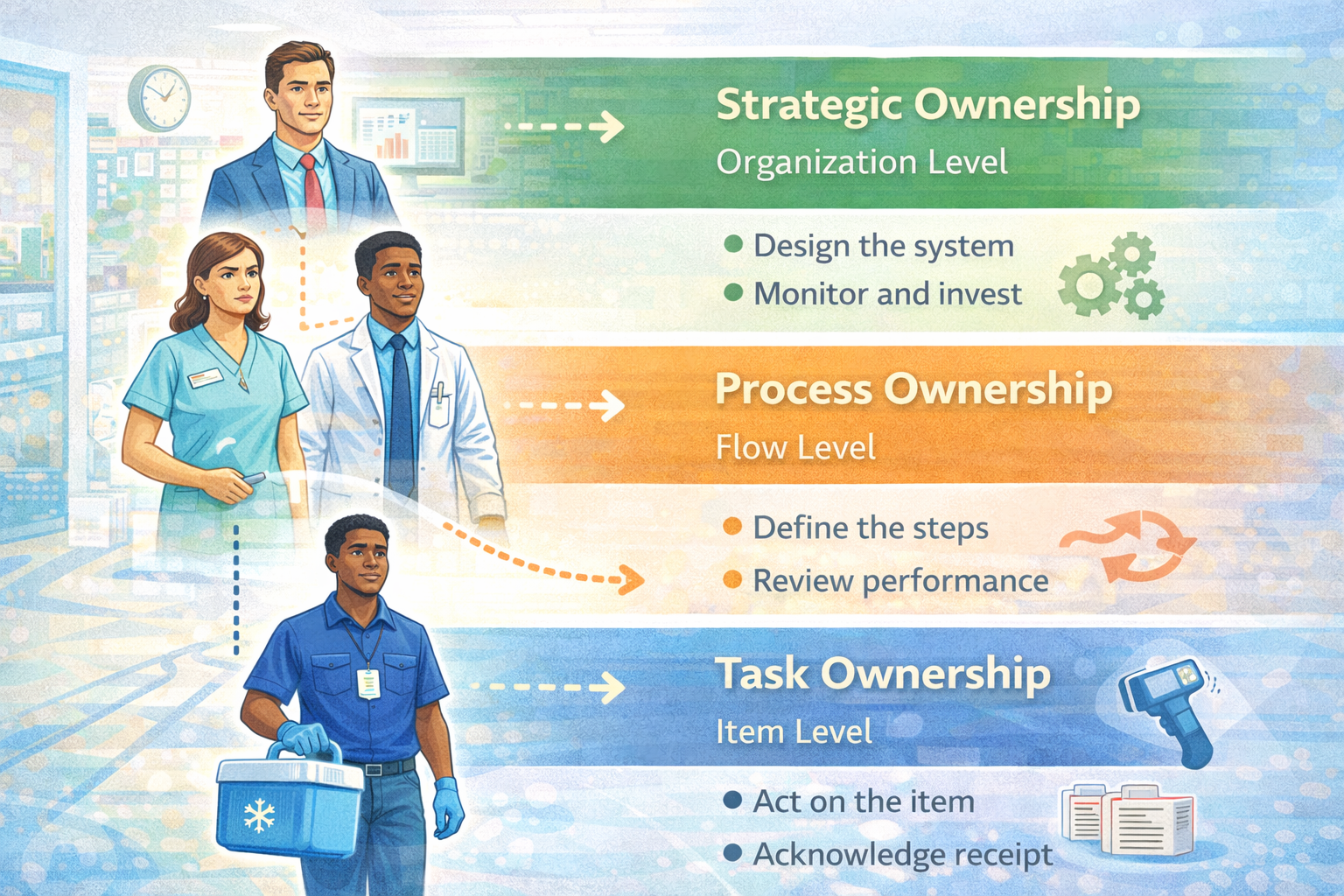

Defining Ownership: The Three Levels of Responsibility

To get out of the "everyone and no one" trap, it helps to define responsibility at three levels:

Strategic ownership – Who designs and governs the hospital transport system?

Process ownership – Who is responsible for ensuring a given flow (ED→Lab) works reliably?

Task ownership – Who, at a moment in time, is responsible for moving a specific item?

1. Strategic Ownership – The System Level

Strategic ownership sits at the organization level:

Deciding how porters, nurses, and automation fit together in a hospital transport system

Setting policies on what can go via tube vs manual vs courier

Approving investments in tube network design, staffing, and technology

Monitoring performance metrics and driving improvement

Many hospitals assign this to a combination of Operations/COO, Facilities or support services leadership, and Lab and pharmacy leaders (for clinical items).

The key is to make it explicit: someone is accountable for the design and performance of internal logistics, not only for purchasing equipment.

2. Process Ownership – The Flow Level

Below that, you need owners for specific flows, such as:

ED ↔ Lab (STAT and routine specimens)

OR ↔ Blood Bank

Pharmacy ↔ ICU and wards

Clinics ↔ Central Lab

Process owners help define SOPs (what's moved, how, and by whom), coordinate training and issue resolution across departments, and review performance for their flow (average ED→Lab transport times).

These owners are often clinical + operational dyads (ED nurse leader + lab manager) supported by logistics/transport services.

3. Task Ownership – The Item Level

Finally, for any specific specimen, medication, or blood product:

Who is responsible for packaging and dispatch?

Who is responsible for moving it (porter, nurse, courier, tube)?

Who is responsible at the receiving end for acknowledging and acting on it?

Clarity here prevents assumptions like "I thought someone already sent that" or "I figured the porter would get it."

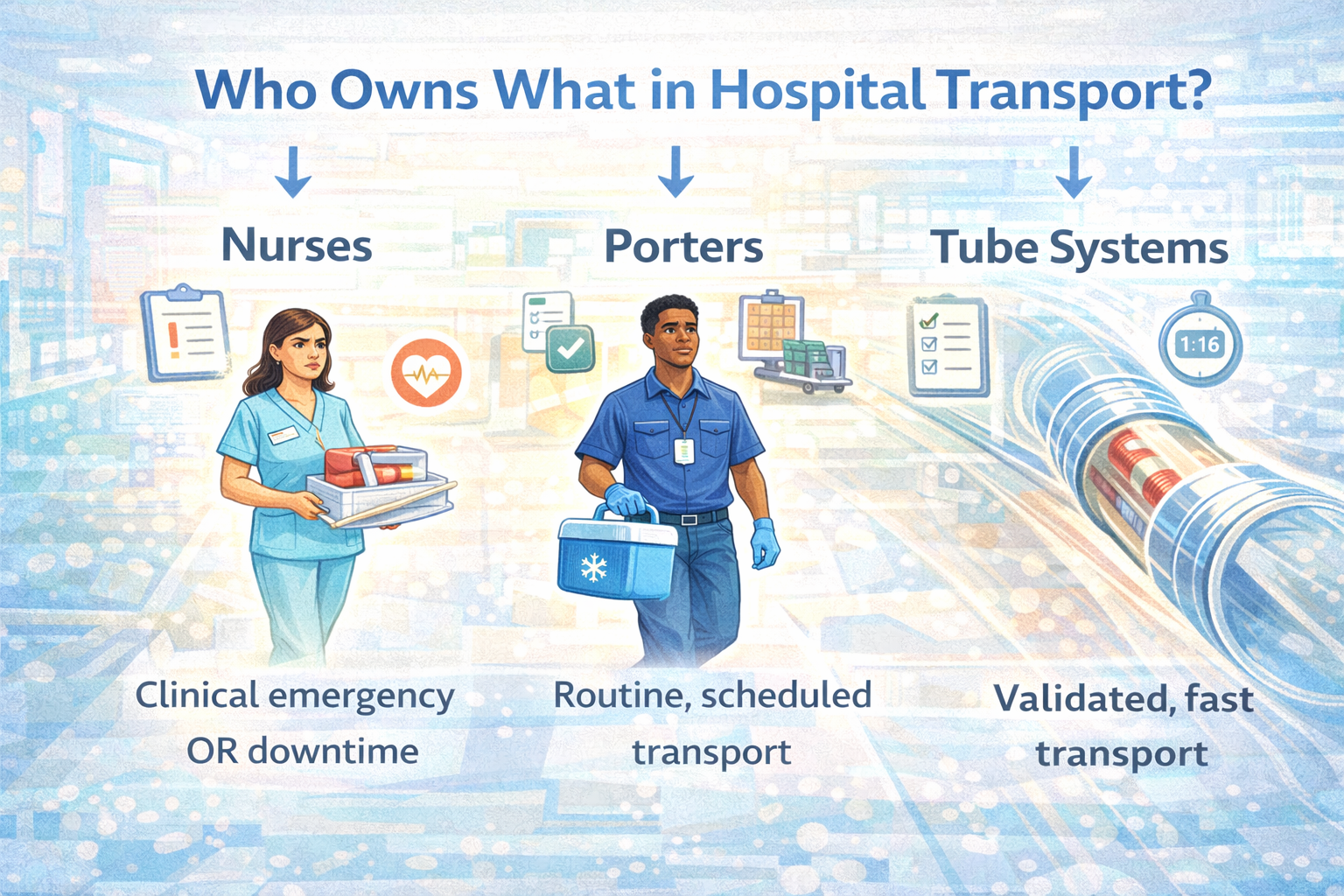

Nurses vs Porters vs Tube Systems: Getting the Mix Right

A common pain point is nurses acting as default transporters of last resort. That's not what they're hired or trained for, and it pulls them away from direct care.

When Should Nurses Transport?

Nurses and clinical staff should typically move items only when:

It is clinically critical and faster than waiting for normal processes (walking a life-threatening specimen during a tube outage).

A backup or downtime procedure specifically assigns them this role.

This should be the exception, not the norm.

What Should Porters Own?

Porters (or equivalent logistics staff) should own routine, predictable transport of non-critical and many urgent items, follow defined routes and schedules tuned to actual demand, and provide reliable backup when automation is offline or items can't go via tube.

If it's not clinically necessary for a nurse to carry it, and it's not appropriate for the tube, porters move it.

Where Do Pneumatic Tube Systems Fit?

Validated pneumatic tube systems should own the majority of appropriate, time-sensitive specimen and document transport within a building, provide fast, consistent routes between ED, OR, ICU, wards, lab, and pharmacy, and reduce reliance on both nurses and porters for many high-volume flows.

How it works:

If an item is on the "safe to tube" list, and a station is available, tube is the default.

Porters handle exceptions and items that can't be tubed (by policy or design).

Nurses step in only when pre-defined exceptions or failures occur.

Making Ownership Concrete: RACI for Critical Flows

One practical tool is a simple RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) for key flows.

For example, ED → Lab (STAT blood specimens):

Responsible: ED nurse / phlebotomist to collect, label, and dispatch via tube

Accountable: Lab manager + ED nurse manager (process owners for the flow)

Consulted: Transport services and tube system administrators (for route design and performance)

Informed: ED physicians and operations leaders (about performance, changes)

For OR → Blood Bank (blood products):

Responsible: Blood bank staff to package and dispatch; designated porter to deliver (if not validated for tube)

Accountable: Transfusion service director + perioperative nurse leader

Consulted: Transport services, risk management

Informed: Surgeons, anesthesiologists, OR leadership

When RACIs are written down and shared, it becomes clear who the true transporters are in each context, and who needs to change behavior when performance slips.

What Happens When No One Owns the Journey?

Without clear ownership, hospitals see predictable problems:

Hidden nurse workload: Nurses routinely leave units to move items, impacting staffing and patient experience.

Variable TAT: Similar tests have very different turnaround times depending on unit habits.

Safety incidents: Misrouted or delayed samples, meds, or blood products.

Underused automation: Tube systems present but not trusted or used consistently.

These aren't only operational annoyances. They can directly impact patient outcomes and staff retention.

Steps to Clarify and Strengthen Transport Ownership

You don't need a massive reorganization to improve. Start with a few focused steps.

1. Map Current Roles and Pain Points

For key flows (ED↔Lab, OR↔Blood Bank, Pharmacy↔ICU):

Who currently moves what?

When do nurses step in?

How often are porters involved?

How often is the tube system used?

Gather frontline stories:

"We usually end up walking it because…"

"We don't use the tube for that because…"

This reveals where assumptions and reality differ.

2. Define Target Roles and Backups

For each flow, decide:

Primary transport method (tube, porter, courier, nurse).

Secondary method when the primary is unavailable.

Who decides when to switch and how that is communicated.

Write these decisions into SOPs and quick-reference guides, orientation and training materials, and tube station and lab signage.

3. Align with Your Lean Transport Design

Link role clarity directly to your lean transport strategy:

High-urgency items → tube or dedicated porters, with nurses only as emergency backup.

Routine items → tube and structured porter routes.

Low-urgency items → scheduled porter and materials management flows.

Ownership and process design should reinforce each other.

Atreo's Perspective on Ownership and Transporters

Atreo's work with hospitals goes beyond installing systems. We help clarify who owns what in internal logistics, so equipment and people work together.

What that includes:

Facilitating "who moves what, when, and why" workshops with operations, lab, pharmacy, nursing, and transport services.

Designing pneumatic tube networks and policies that fit clearly defined roles.

Providing data (tube usage, travel times) that shows who is moving what and where patterns don't match the plan.

The goal: make sure every critical item has a clear, reliable journey owner from origin to destination.

Key Takeaways: Owning the Journey of Critical Items

"Transporters in hospitals" include nurses, porters, tube systems, and couriers. All play a role.

When no one clearly owns the journey, delays, waste, and safety risks increase.

Ownership should be defined at three levels: strategic (system), process (flow), and task (item).

Nurses should not be default couriers. Validated tube systems and structured porter roles should carry most of the load.

Simple tools like RACIs, clear SOPs, and visible metrics help keep responsibilities aligned.

Next Step: Talk with Atreo About Transport Ownership

If you’re seeing nurses walk labs or meds long distances, confusion over who should move what, or an underused tube system, a conversation can help.

Review who currently moves critical items across your hospital

Spot gaps and overlaps between nurses, porters, and pneumatic tube use

Discuss practical steps to clarify ownership and improve reliability

Frequently Asked Questions About Transporters in Hospitals

Should nurses ever be primary transporters?

Only in very specific, defined circumstances (during a downtime or when a life-threatening item must move faster than any other option). Nurses are exception handlers, not routine couriers.

How do we get staff to trust the pneumatic tube system?

Trust is built through proper design and validation (especially for specimens and meds), clear policies about what can safely be tubed, training and communication about results and performance, and rapid response when issues are reported.

When staff see that tubes are safe, fast, and supported by leadership, usage increases naturally.

Who should "own" the hospital transport system overall?

Typically, strategic ownership sits with operations/COO, supported by facilities/support services, lab, pharmacy, and nursing leadership. What matters most is that ownership is explicit, and that this owner convenes the right stakeholders to design, monitor, and improve the system.