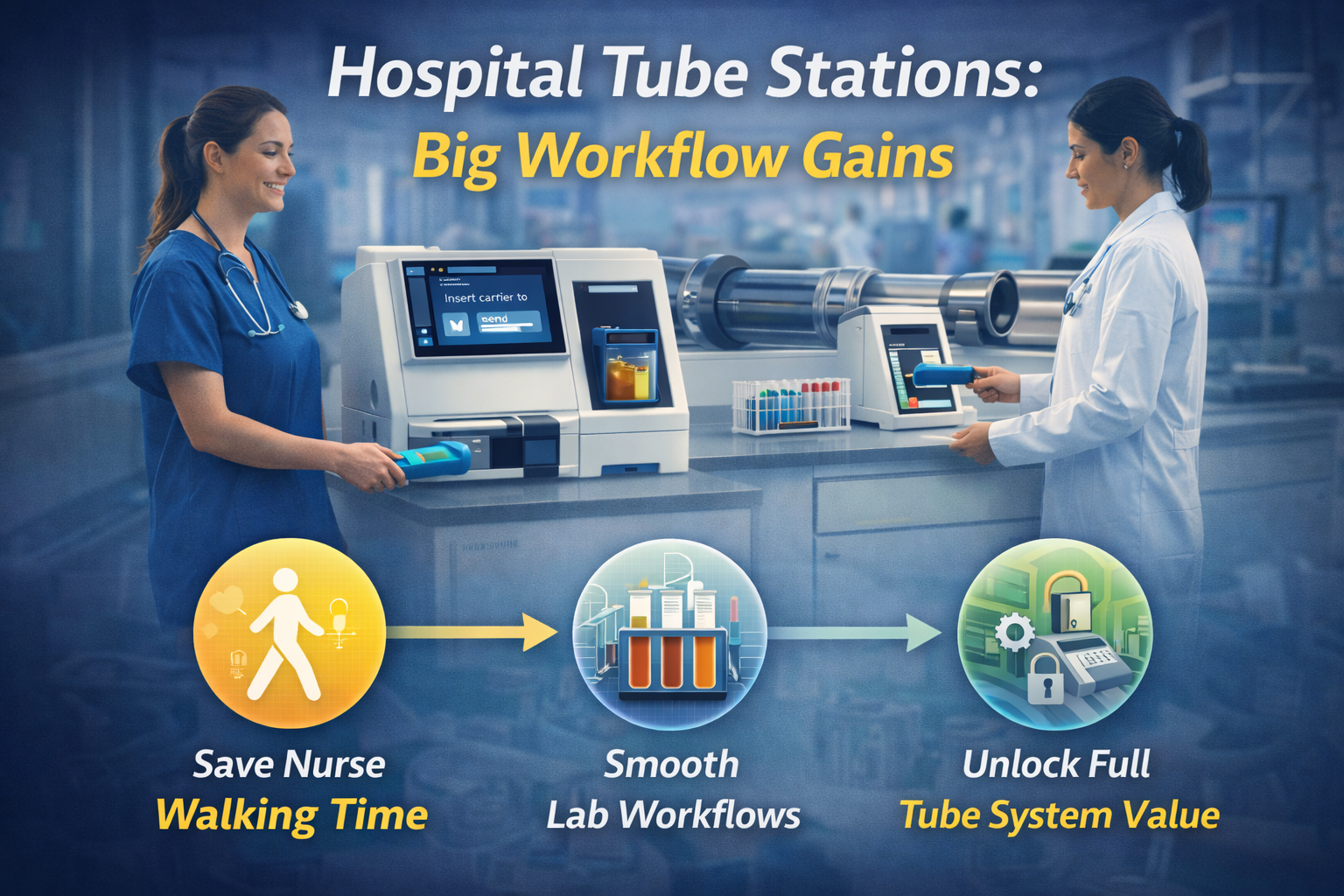

Hospital Tube Stations: Small Footprints, Big Gains in Nurse and Lab Workflows

When people talk about a hospital tube system, they usually picture the hidden network of pipes behind the walls.

But for nurses and lab staff, the system is much simpler:

It's the hospital tube station they use (or avoid) on every shift.

Where that station sits, how it's configured, and how easy it is to use will determine whether your pneumatic network:

Actually saves nurses time, or just looks good on a floor plan

Smooths lab workflows, or creates new peaks and gaps

Feels safe and trusted, or like a risky shortcut

This article zooms in on tube stations in hospitals—not the whole network—and shows how small, practical design decisions at the station level can deliver big gains in nurse and lab workflows.

Why the Station Matters More Than the Pipes

From a project perspective, it's tempting to focus on:

Routes and risers

Blower capacity

Control logic

All critical. But on a busy ward, the questions are more basic:

"Is the hospital tube station close to where we actually draw blood?"

"Can I send this specimen quickly without leaving the patient too long?"

"When a carrier arrives, does someone see it immediately?"

If the answer is "no" to any of these, you get predictable behavior:

Nurses walk specimens instead of tubing them.

Carriers sit unopened in the station.

The lab sees spikes when someone finally empties a backlog.

The station is where your investment in a hospital tube system either connects cleanly to real workflows—or misses.

Read more here: "How Hospital Tube Systems Actually Work: A Guide for Operations Leaders"

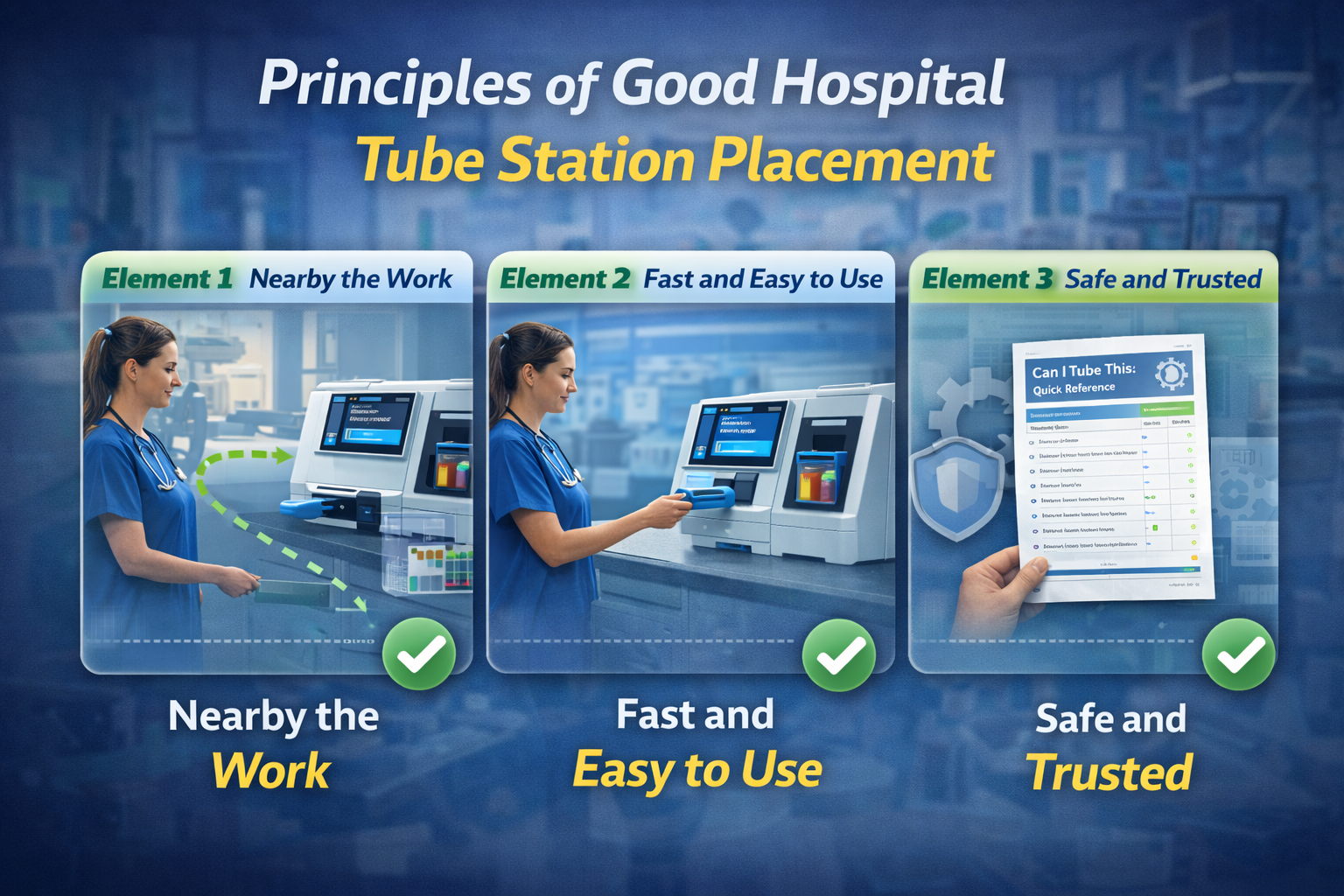

What Makes a Hospital Tube Station "Good" for Nurses?

Let's start with nurse workflows. From their perspective, a tube station hospital location is either a help or a hindrance.

Element 1 – It's Where the Work Actually Happens

Good:

Station is near the medication room, nurse station, or primary phlebotomy area.

Within a short, safe walk from most patient rooms on the unit.

Not so good:

Station tucked at the far end of a corridor no one uses.

Station placed for construction convenience, not workflow.

Effect:

When the station is "on the way" to normal tasks, nurses use it naturally. When it's a detour, they default to walking items straight to the lab.

Element 2 – It's Fast to Use, Even When Things Are Hectic

Good:

Clear, simple interface (pre‑set destinations, clear priority buttons).

Carriers and inserts for the hospital tube station are stored right next to it.

Quick guides with "what you can tube / what you must walk" at eye level.

Not so good:

Staff have to hunt for empty carriers.

Destination codes are cryptic or different on every floor.

No one is sure what's "allowed" in the tube.

Effect:

The more friction at the station, the more likely nurses are to avoid it in busy moments—exactly when it could help most.

Element 3 – It Feels Safe and Supported

Good:

Clear policies on which specimens, meds, or documents can be tubed.

Training that covers safety, pre‑analytical quality, and what to do if something goes wrong.

Quick response when staff raise concerns.

Not so good:

Old stories about "something breaking in the tube" with no follow‑up.

No visible owner for the station or process.

Effect:

Trust drives usage. If the tube station hospital staff use daily feels risky, they'll go back to porters and walking.

What Makes a Hospital Tube Station "Good" for the Lab?

On the lab side, station design and placement shape how specimens arrive:

One carrier at a time vs big random batches

Clear priorities vs mixed STAT/routine traffic

Predictable vs chaotic peaks

Element 1 – Stations Are Placed with Flow in Mind

Good:

High‑volume clinical areas (ED, ICU, OR, large wards) have direct stations feeding lab‑side stations or buffer areas.

There's a clear mapping: "This station mostly sends this type of work to this lab area."

Not so good:

Many different units share a single lab‑side station, all hitting at once.

Specimens for very different workflows arrive in one pile.

Effect:

Thoughtful station mapping smooths arrival patterns and supports pre‑analytical flow. Random station placement makes lab work harder, even if total travel time is short.

Element 2 – Lab‑Side Stations Are Built for Receipt, Not Just Speed

Good:

Lab‑side hospital tube stations are near accessioning and pre‑analytical areas.

There's a defined role: who empties, when, and how.

Space exists to open carriers, sort specimens, and route them quickly.

Not so good:

Stations are in a cramped corner far from where work happens.

Carriers pile up because "it's no one's job" to empty them promptly.

Effect:

Fast network + slow station handling = no real TAT gain. Station design can either support or undercut lab TAT goals.

Read more here: "Pneumatic Tube Systems in Hospitals: Design Best Practices for 24/7 Reliability"

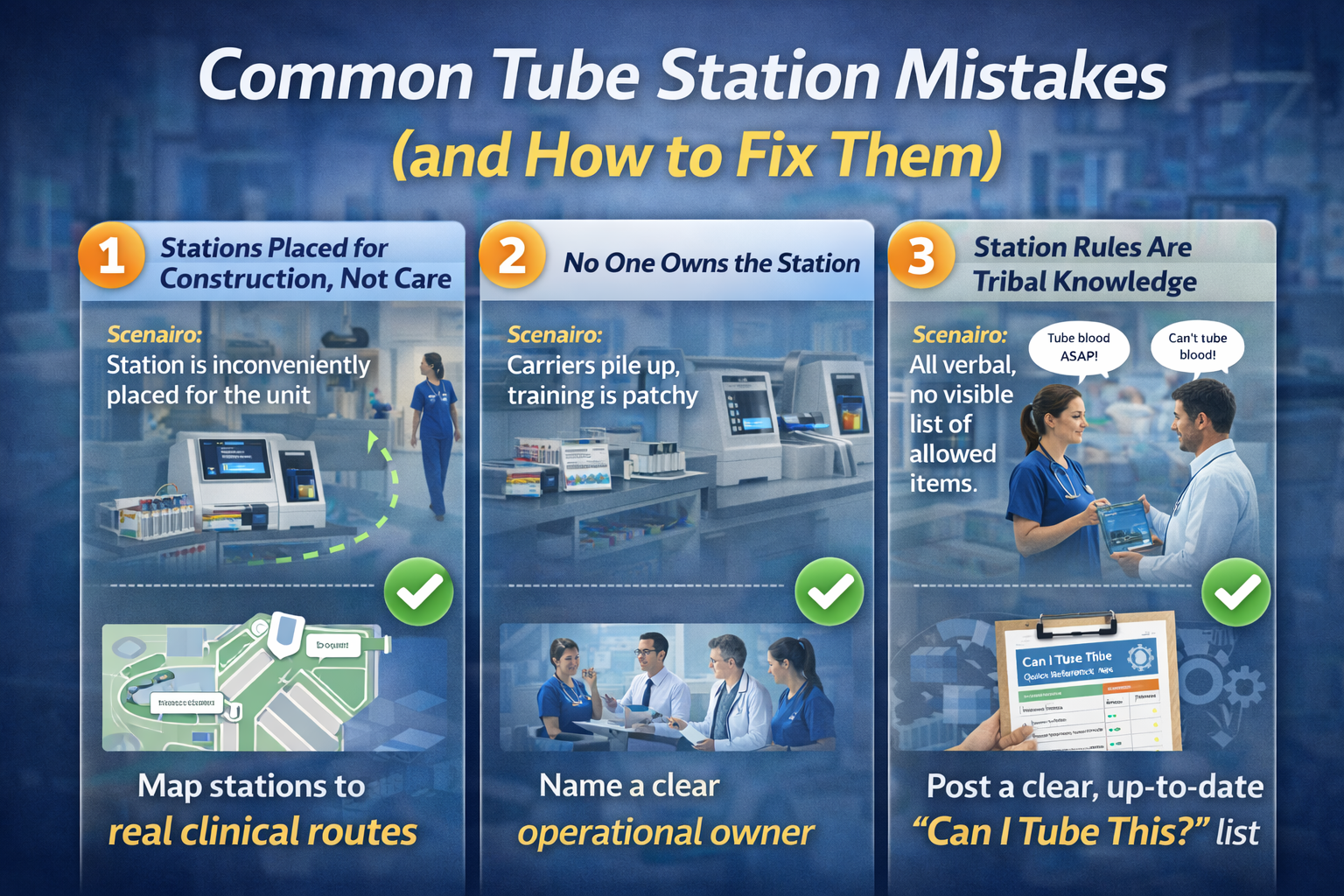

Common Tube Station Mistakes (and How to Fix Them)

To make this concrete, here are patterns Atreo often sees.

Mistake 1 – Stations Placed for Construction, Not Care

Scenario:

The riser is here, so the hospital tube station goes right beside it—never mind that it's 40 meters from the nurse station.

Result:

Nurses walk specimens to the lab during busy times rather than hike to the station. Tube volume is low; ROI looks weak.

Fix:

During design or retrofit, walk the unit with nurse leaders and map real routes.

Where possible, nudge station locations closer to where specimens and meds are actually handled.

In some cases, adding or relocating a single station is enough to change behavior.

Mistake 2 – No One Owns the Station

Scenario:

Facilities "own" the hardware.

Lab "owns" what's allowed inside.

Nursing "owns" unit workflows.

So…no one really owns the station.

Result:

Carriers stay empty or pile up. Training is patchy. Station issues are slow to resolve.

Fix:

Name a clear operational owner for each tube station hospital (often a joint decision between lab/transport and the unit).

Document who:

Empties stations and how often

Restocks carriers and inserts

Escalates issues

Read more here: "Building a Lean Hospital Transport System: From Porters to Pneumatic Tubes"

Mistake 3 – Station Rules Are Tribal Knowledge

Scenario:

Some nurses say, "You can't tube blood products."

Others say, "We always tube them; we've never had a problem."

There's no visible, up‑to‑date list of allowed items.

Result:

Inconsistent practice and avoidable risk. Tube system is either underused or misused.

Fix:

Work with lab, blood bank, pharmacy, and risk to create a clear, validated "Can I Tube This?" guide.

Post it at every hospital tube station.

Include it in onboarding and annual refreshers.

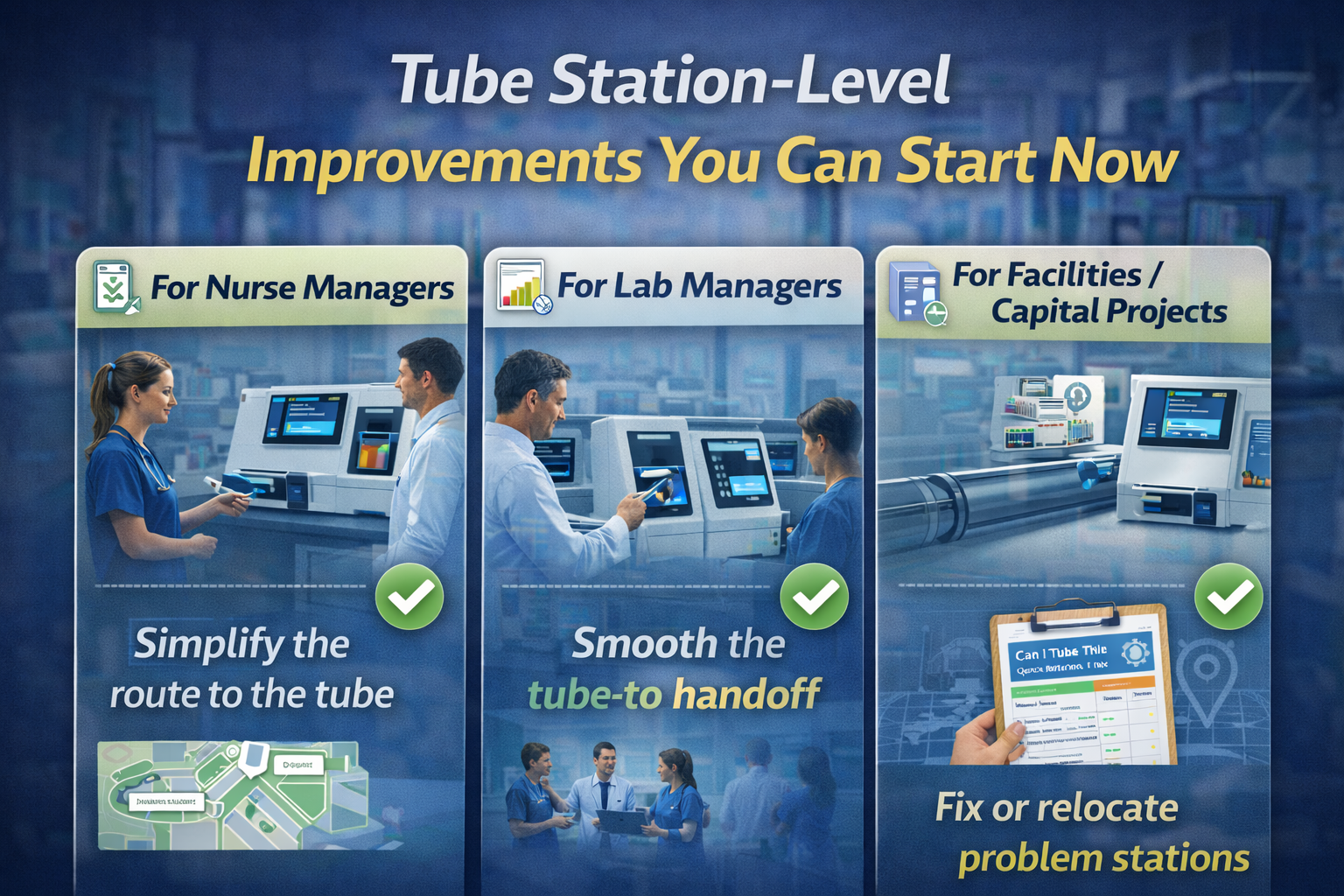

Practical Station‑Level Improvements You Can Make This Year

You don't have to redesign your entire hospital tube system to get better results. Start with the stations.

For Nurse Managers

Walk your unit and note:

How far staff walk from bedside to station.

Where specimens or meds "pause" before being sent.

Ask your team:

"When do you use the tube?"

"When do you walk things instead, and why?"

Use those answers to:

Propose small station moves or additional stations to Facilities/Capital Projects.

Simplify station setup: carriers, inserts, and quick guides within arm's reach.

For Lab Managers

Stand by your lab‑side stations during peak times:

How often do carriers arrive?

Are they opened immediately? By whom?

Do STAT and routine samples mix in the same carrier?

Use that information to:

Adjust staffing or responsibilities for station emptying.

Refine policies on how units should package and prioritize specimens.

For Facilities and Capital Projects

On upcoming builds or renovations:

Involve nursing and lab early when deciding each hospital tube station location.

Test layouts with simple "day in the life" walks before finalizing.

For existing systems:

Identify underused stations and ask why.

Explore small relocations or reconfigurations that would make them part of real workflows.

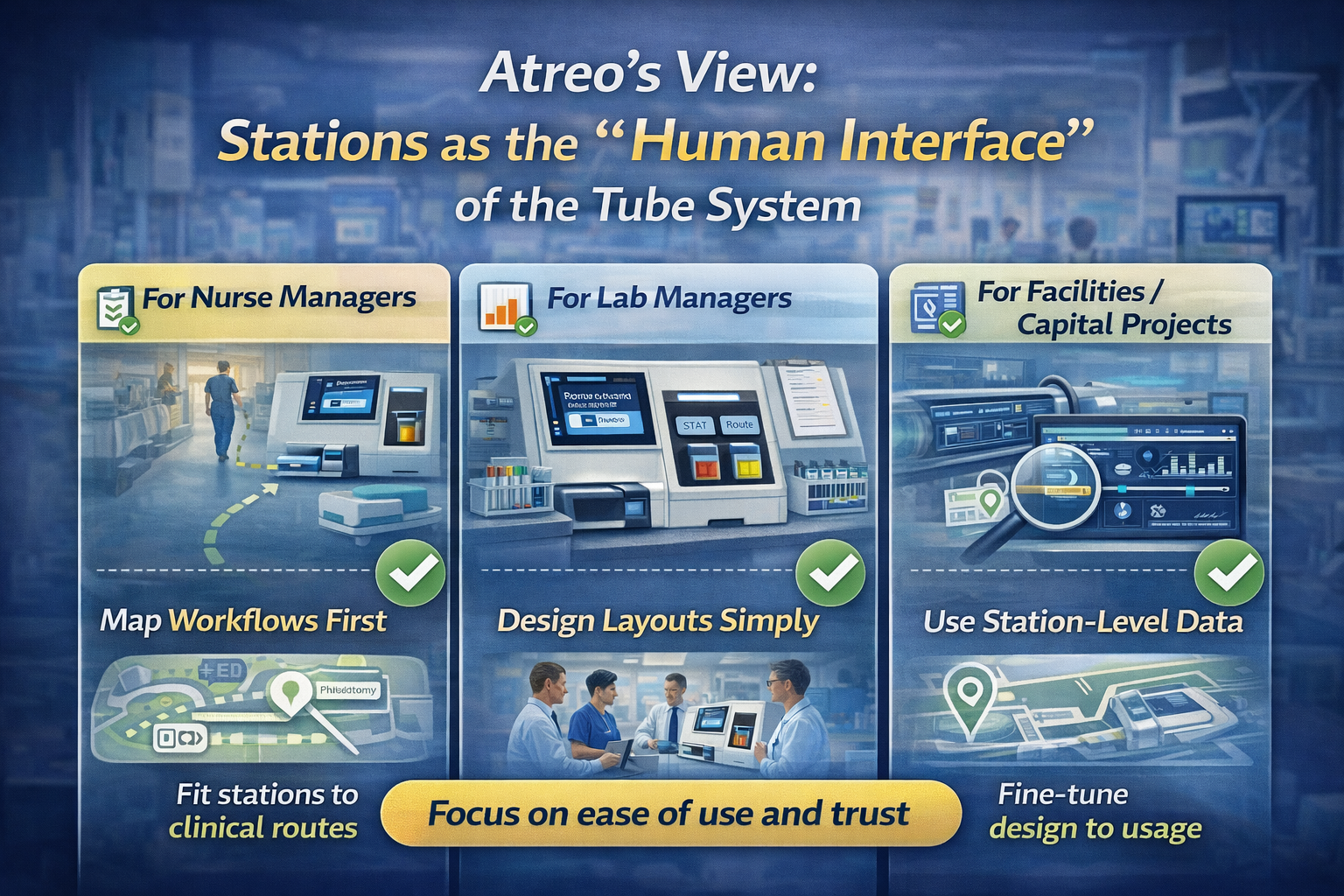

Atreo's View: Stations as the "Human Interface" of the Tube System

Atreo treats the hospital tube station as the face of the system.

In work with hospitals, that looks like:

Mapping nurse and lab workflows first, then placing or relocating stations to fit them.

Designing station layouts (carriers, inserts, signage) to be simple and intuitive.

Using station‑level data—volume, timing, routes—to see where design and behavior don't match.

A well‑designed network with poorly placed or poorly used stations never delivers its full value. But when stations are easy to reach, easy to use, and clearly owned, the hospital tube system becomes a trusted part of daily care.

Key Points for Leaders Focused on Tube Stations

For staff, the hospital tube station is the system. If it's hard to reach or confusing, they won't use it.

Station placement and design have a direct impact on nurse walking time, lab TAT, and trust in automation.

Clear ownership and simple, visible rules ("what you can tube") reduce variation and risk.

Small changes at the station level—location, layout, responsibilities—can deliver outsized gains compared to big capital projects.

Next Step: Talk with Atreo About Your Tube Stations

If your hospital has a tube network but stations that are underused, mistrusted, or awkwardly placed, there's likely value trapped in your current design.

Contact us to:

Review how your hospital tube stations line up with real nurse and lab workflows

Identify quick wins in station placement, layout, and responsibilities

Discuss how station‑level changes can support broader lean hospital operations and TAT goals

Frequently Asked Questions About Pneumatic Tube System Cost

What is a hospital tube station?

A hospital tube station is the visible “front end” of a pneumatic hospital tube system—the point where staff load and unload carriers. For nurses and lab teams, the tube station is the system they interact with every shift, so its location, layout, and ease of use strongly influence whether the tube network is actually used.

Why does hospital tube station placement matter so much?

Placement determines whether the tube station is on a nurse’s natural route or a time‑consuming detour. Stations located near nurse stations, medication rooms, and primary phlebotomy areas are used more often, which reduces walking time, speeds specimen transport, and supports better lab turnaround time (TAT).

How do tube stations impact lab turnaround time?

If a tube station hospital location is inconvenient or poorly supported, nurses and porters tend to walk specimens to the lab or hold them in batches. That creates irregular peaks and delays. Well‑placed, well‑run stations help specimens move steadily from units to lab‑side tube stations, smoothing pre‑analytical flow and making lab TAT more predictable.

What makes a hospital tube station “good” for nurses?

A good hospital tube station is close to where care and blood draws actually happen, quick to use even when the unit is busy, and clearly safe. That means simple controls, carriers stored at arm’s reach, a visible “what you can tube” guide, and clear support when concerns arise. When those elements are in place, nurses naturally choose the tube over walking.

Who should own tube station operations?

Facilities may own the hardware and the hospital tube system design, but day‑to‑day performance depends on shared ownership. Successful hospitals name a clear operational owner for each station—often a joint agreement between lab/transport and the unit—so responsibilities like emptying carriers, restocking inserts, and resolving issues are defined and monitored.

Do we need a full tube system redesign to improve station performance?

Not necessarily. Many hospitals see big gains from small, station‑level changes: moving an underused station closer to real workflows, adding a new station in a high‑volume area, simplifying layout and signage, or clarifying responsibilities. These targeted adjustments can unlock more value from the existing hospital tube system without a major capital project.